The Future of Design is Still Personal: Reaching Toward True Adaptation

If the people who we now call “users” could derive their own experiences by expressing their intention, how radically different could our work, as designers of all types, be?

The discipline of design has historically produced fixed products. Even the term "product" implies the end of a process, or something that is completed and typically unchanging. But we know that the intent of the designer and of the person experiencing the design are engaged in an ongoing conversation. Digital products have drastically increased the pace of that conversation, introducing faster iteration, new modes of interaction, and – importantly – space to imagine a future in which a person's intent directly defines their experience of digital interfaces. This essay connects historic conceptions of interface and adaptable design with contemporary developments and visions, looking toward a truly adaptive future that transforms “users” into individual creators by directly enabling the expression of their intent.

How many times have you seen an image that describes the experience of a UX designer?

Is ketchup the best metaphor?

The image that has probably been the most pervasive, vacillating between ironic and earnest at various moments, is that of two bottles of ketchup. On the left, there’s a glass bottle that stands upright with a metal screw top lid. The kind of bottle you have to hit with an open palm or stick a knife in to “get things going.” But, the image implies, it’s aesthetically nice. It stands for the type of design that looks nice, regardless of its impact on our experience - there is an implicit value statement in the image that this bottle, helpfully labeled “UI” is mostly concerned with visuals and sacrifices all else.

On the right, a plastic bottle with the lid facing down. This one squirts, and gravity helps the ketchup stay near the opening. The lid is even bigger for better balance. It is, ostensibly – given the label “UX” – a bottle whose primary concern is ease of use, a good experience, and more ketchup. The image of course can’t illustrate that this bottle you still need to shake beforehand, will probably fall over at some point, gets crusty around the opening, and is made of single-use plastic that is, in all likelihood, going to be dumped in the ocean.

What does this mean, actually?

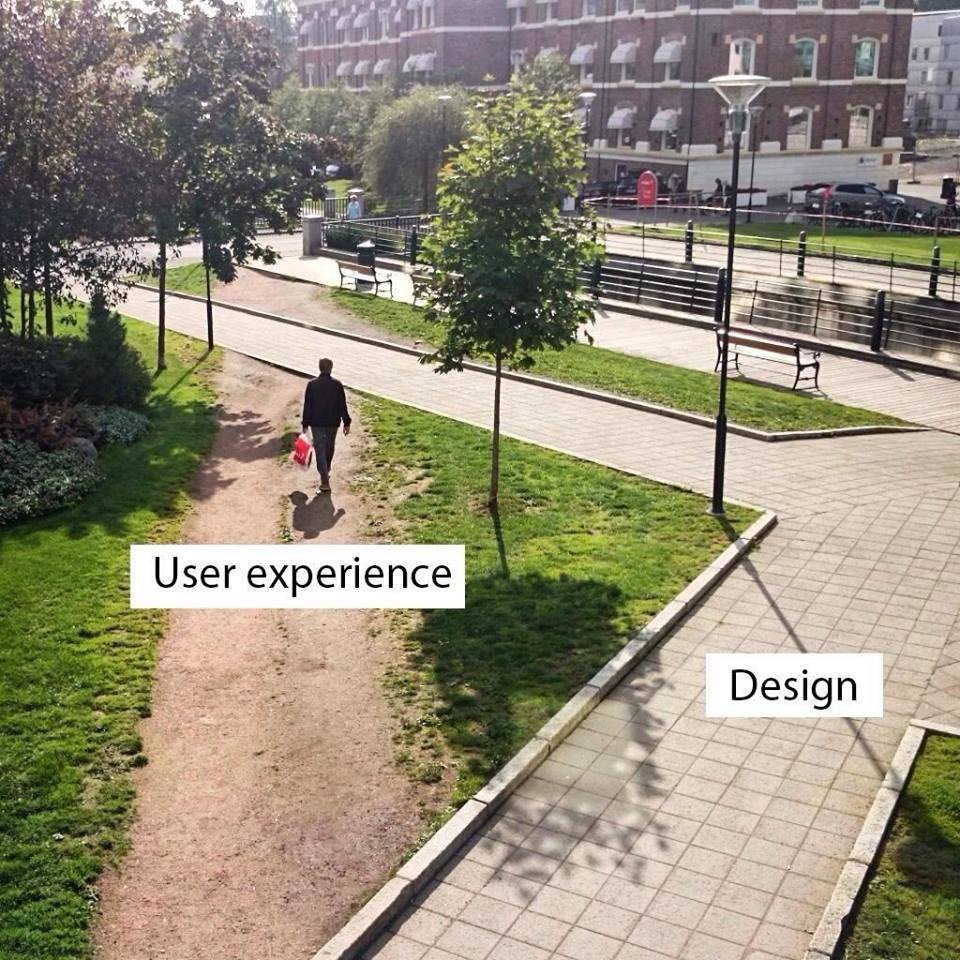

Then there’s the “desire path” image, showing a well-trod dirt path cutting through grass next to a perfectly maintained sidewalk. The sidewalk is instructively labeled “design,” again aesthetic, full of visual function and meaning, clearly representing a design intent, and the desire path is labeled “User Experience.” This image, too, is loaded with implicit beliefs. The desire path would tell us that perhaps a designer should have made a diagonal sidewalk instead of a perpendicular one, or perhaps that user experience really means that the user will do whatever they want to accomplish a task, no matter how carefully we’ve placed our bricks on the path.

It’s worth considering that this gif was clipped from an episode of the show Gravity Falls in which the men pictured are revealed to be imprisoned clones.

Finally, though I’m sure this isn’t the last image that comes to mind, there’s the gif of a guy with a glass of water who can’t seem to take a drink¹ - a straightforward task like drinking water is made to look impossible even though to us, as viewers, the answer is right there. If we’re viewing as designers, we see that someone has designed a glass for holding water and putting it to your mouth, and we give a knowing chuckle to the representation of a user who just can’t figure it out.

These images feel relatable to us at different stages of the design process, and can provide some much needed comic relief, but they share another common factor with one another: they frame the intent and context of the user as an aberration, something to be worked around, to predict and influence, to standardize or, in the worst case, to ignore.

If these images are any kind of touchstones for our understanding of our discipline, we can probably use them for some critical reflection, too. Our work creating interfaces doesn’t typically deal with ketchup bottles, sidewalks, or glasses of water. The technology we use to implement an interface is digital. The metaphorical ketchup bottle we’re producing doesn’t even have to have a fixed shape – ours is customizable. Its shape, color, size, elevation, placement, are all easily changeable. Likewise our sidewalks can be reconfigured for specific use-cases or tasks. A trail through nearby grass shouldn’t be a problem or an interesting side-effect, it should be something we welcome and facilitate. Why can’t someone drink out of the bottom of a glass of water, when the glass itself is virtual?

If we imagine this happening in actual space it sounds a little outlandish. We understand these objects to be the fixed result of a process of production. Even the word “product,” which we certainly use to describe our work as designers and developers, implies something that is produced, something lying at the end of a process rather than in the middle or the beginning or somewhere totally outside a process of creation as we would currently conceive it. As such, most products are resistant to change. They’re inflexible; their properties are unbending; put simply, they can’t adapt.

Ketchup rolls along a mass-production line.

Mass Production

Many if not most products we encounter today are also understood to be the result of mass production, a process that owes its speed and efficiency to the standardization of the objects it produces. To make a new type of ketchup bottle, you need new molds for glass or plastic, new designs, machined parts that can precisely reproduce the bottle over and over again. Over time, incremental improvements are made in response to material costs, manufacturing processes, customer response, and aesthetic trends. That is to say, all products are the outcome of a conversation between a creator and a person experiencing the creation. But most people will be using the same ketchup bottle for a long time before a new one comes along.

With the advent of digital or virtual products – that is products that are reproduced with low-level materials like electricity rather than higher level physical materials like glass or concrete – the pace of this conversation has quickened significantly, and has the ability to become more dimensional and inclusive than before. As people making products for a digital platform, we have an unprecedented ability to iterate on ideas and change products over and over again, fine-tuning them to match our goals and the goals of our users. Despite this, we are still essentially manufacturing new ketchup bottles really really really fast, rather than changing something in the fundamental discipline of I guess, in this metaphor, containing and dispensing ketchup; something that would provide the basic capability of dispensing ketchup, but leave the details – grip, volume, weight, shape, color – up to each person’s own realities. Keller Easterling, in a discussion of her book, Extrastatecraft put it best:

“You don’t square up to every weed in this field with a righteous fight; you change something in the soil.” ²

Our collective gaze in designing digital products is fixed on systems, standardization, and the notion of “best practices” to solve problems. We have a set of tools that we continually apply to what is, fundamentally, an immeasurably nuanced set of questions and needs. When we finish using the tools, we distribute linear updates. In other words, we, too, practice mass production, and address each weed in the field with incremental improvements. In actual application of our practice, it isn’t the conversation that’s gotten faster – it’s just the distribution.

And as we push more updates, we create more products. And these responses to the externalities I mentioned before can only happen in aggregate because we are only shipping one app or product at a time. An aggregate approach means that, in all likelihood, no one thing is designed specifically for any one person.

On the other side of things, as people called “users,” we find ourselves trying to find and fit into workflows, developing new intentions in order to satisfy our existing ones by “learning” to use interfaces, keeping up with abstract patterns like navigation or gesture controls. This experience is especially acute for people who haven’t been included in the evolution of interface design, or who might be encountering these kinds of interfaces for the first time.

As a response to this, in 2015 and 2016 when I began working on Project Phoebe, which was my first foray into imagining other futures for our discipline, I discussed the need for digital interfaces to make themselves prolific, becoming what each person needs rather than what an aggregate of many people may need.

I want to revise that approach by adding that interfaces should be based not only on individual needs but also intentions - those that are, crucially, not the ones established by designers. Interfaces should follow rather than shape the needs and intentions of the user. The process of moving toward this goal will fundamentally transform our approach to designing interfaces.

The shifting role of design

But let’s catch our breath and consider how we talk about our work for a moment. For the designers reading this, some of us may consider ourselves to be “product designers,” the creators of products which, as we discussed, lie at the end of a process. We “design” the results of that process, crafting a path to reach them and a product that can, ultimately, reproduce that path for other people. Some of us prefer the term “UX designer,” and we are the creators of something that is experienced by users, or experienced through use. We can also be “UI designers,” who build the substrate interface upon which the product can reproduce its results. Still others are “interaction designers,” and we say that we are “creating” interactions that people can execute with our digital objects, invisibly guiding their eyes, hands, and thoughts as an architect might conceive of guiding a body through space. Within and without these categories there are numerous other specializations and generalizations, but the semantics of our titles are not important.

In all these scenarios, we are operating with a mentality shaped by the received knowledge of our industry, which is itself shaped by the received knowledge of the capitalist organization of our economies. The mentality is one that relies on the idea, mentioned earlier, that user intent is something that needs to be predicted, documented, worked around and, most insidiously, influenced by the product makers; it’s an approach that sees consumption - rather than creation - as a primary mode of experiencing the world, and this is starkly reflected in our work.

To begin to break our discipline out of this rut, consider what it might be like if the people who we now call “users,” were instead “creators.” If the people who are now expected to passively experience and consume a product, dutifully reproducing results designed by our intention, actually could derive their own experiences by expressing their intention. How radically different could our work, as designers of all types, be?

Let’s explore that.

What is “interface?”

In a SPAN 2015 session called The Interface³, architectural historian John Harwood discussed the history of chair design as a means of understanding the object/subject relationship between people and the objects that govern our experiences of the world. The talk began with Marcel Breuer, a modernist architect with a prolific portfolio of furniture produced during his time at the Bauhaus.

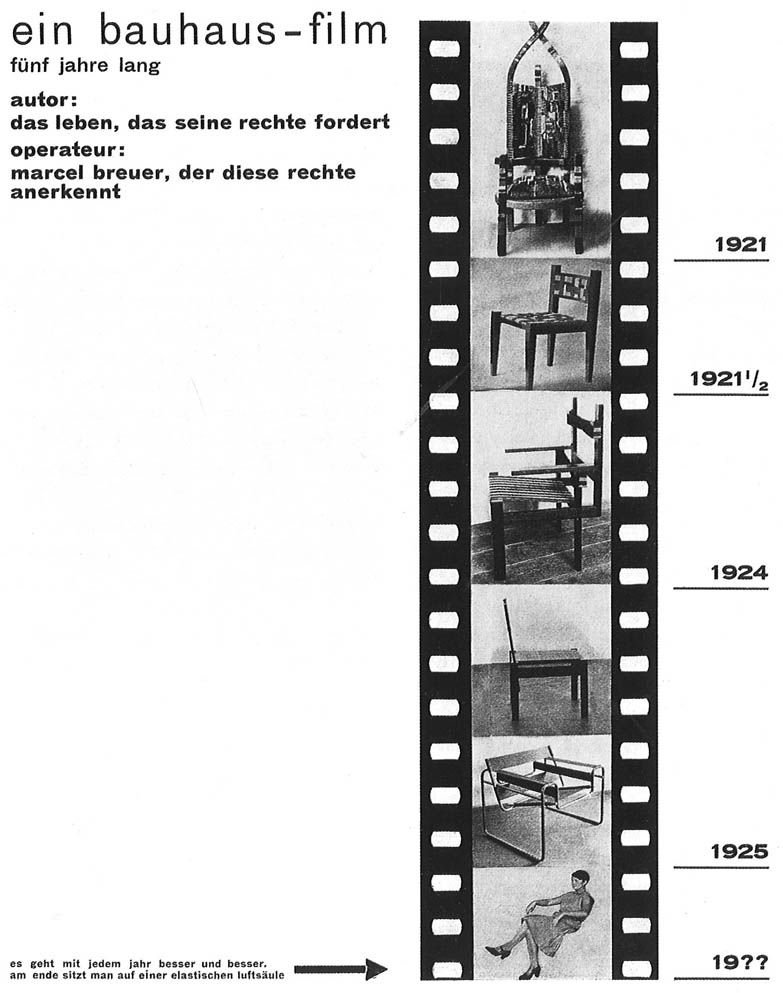

Breuer’s 1926 reflection on the future of (furniture) design.

Breuer understood the peculiarity of the dynamic between creator and experiencer, illustrating in a 1926 poster⁴ that “[chair design] gets better and better every year. In the end, one sits on an elastic air column.” The humor of imagining that what we consider a “chair” will be transformed into something that is indeed so elastic that it no longer physically exists must stand side-by-side with the lived experience of all chair-sitters that actually, chairs are often not that comfortable, and that one chair has difficulty supporting multiple needs.

Photos by @whoishaleylawrence, @xcrap, and @sweetspotphoto on Unsplash

Even if it’s great for one purpose like seating many people at an event, or fitting into a corner, or looking great on the patio, it might not support you after a long hike, or hold you and your child as you read a book together, or survive bad weather. An invisible, elastic air column really doesn’t sound so bad.

“Interface” is a dance.

This example underscores that the concept of “interface,” as a description of the dance between subject and object – between human and technology – has been floating around for a long time. The chair was understood by Breuer and others to be one interface – something nominally, if not practically, designed with a human in mind, but ultimately, as a static object, exerting its own object will on the person who ends up sitting in it.

Photos by @fesh00, @octadan, and @charlesdeluvio on Unsplash

Architecture, the tangible outcome of which is itself interface, already recognizes the potential here, edging physical products toward a malleable, dynamic mode of experience through movable elements like shoji panels, curtain walls, and other components that allow occupants to easily reconfigure physical space in a way that a chair usually cannot.

We know, as creators of digital environments, that we have an exponentially larger capacity for expressing this type of potential in our own work. An interface in actual space – as opposed to digital or virtual – could be the physical contact between a body and a chair, while ours is often finger-, voice-, eye-, and ear-to-device. Consider that a chair rarely learns anything from how a person sits, or where they want to put their feet, or what they can do with their hands.

Footage from The Fabricant

Designing for Self-Actualization

Kerry Murphy is co-founder of the Fabricant, a studio that produces virtual couture; that is, clothing that exists only in virtual space. When designing garments for virtual space, Murphy says that his studio uses the “language” of physical clothing design, while materials are unbound by normal physical constraints. The “raw materials,” he says, are data. The texture, strength, color, weight, and dimensions of fabric are expressed as ones and zeros. In our discussion on Design Notes⁵ Murphy also divulged his experiences creating and manipulating a photo-realistic virtual avatar of himself. Through trying on challenging garments and programming his body to perform heretofor impossible movements, Murphy uncovered something about the self-actualizing potential of digital or virtual experiences.

“My first reaction was like- like, ‘No, I would never wear that,’ but my second reaction was like, ‘But hey, what if? … How would I feel if I would go out into the open with this weird clothing that I'm wearing in my digital life?’ All of the sudden, I started becoming much more open to things that I was not necessarily open to before.”

This embodiment allowed him – as it allows others – to reflect on what it would be like if their actual-world intentions could be easily satisfied. More than that, it drew into question the subject/object relationship that Breuer and others would have assumed before the advent of sophisticated digital interface. Suddenly, the object will of the images being presented to Murphy was actually aligned with his will as a subject; directly shaped by it, in fact. The conversation became two-sided, and both were in agreement.

Tom Boellstorff echoes this dynamic in his ethnographic work on virtual worlds, including his 2015 book, Coming of Age in Second Life⁶, noting that, “corporations who simply saw Second Life as ‘interactive’ misrecognized interactivity for creation: the cultural logic in play was not that residents interacted with a commodity and its producer, but that they literally produced what they consumed through self-actualizing acts of creation.” The implications for virtual worlds – where residents can create their own body, clothing, house, and decorations using data as raw material – are clear: the resident of the virtual world exists as an entity solely through their own acts of creation within that world. Their intention for their own presentation and integration into the social milieu of virtual space is directly manifested through the world itself and the interface that governs life in virtual space.

Zooming back into our own work from here, (work which largely manifests itself on screens in the actual world) we can begin to get a better understanding of the work’s self-actualizing potential, and what it may look like to give individuals the power to create their own experiences with our products.

In the same text, Boellstorff asserts that intentional creation is not the only type of creation we have to consider when studying how intent and identity manifest in design. Besides intentional, explicitly planned creation, emergent or situational creation plays an equally important role in an individual’s virtual presence and actions. This Boellstorff compares to Swiss linguist Ferdinand de Saussure’s distinction between grammar and speech – the planned logic and mechanics of language against the practical application in everyday life. Boellstorff notes that the concept of design itself “presumes intentionality” on the part of the designer, a possible “misunderstanding of the present” that hinders our ability to imagine the future, a future, by the way, that Boellstorff admits – as we all must – is ultimately unknowable.

If we want to transform the discipline of design, then, by giving it a new foundation – one that doesn’t entirely rest on our intentionality as designers – we have our work cut out for us.

Information + Action

Right now, the digital interfaces we find on personal devices can be boiled down to two primitives. These two primitives, which I’ll call information and action are the building blocks of what we would now call user experience. From these primitives, we derive components. Components come together into UI regions, UI regions comprise screens, and screens comprise flows, and flows comprise apps. You’ve almost certainly seen it broken down like this before, from small abstracted concepts to large practical applications – I would consider all such models valid propositions, with the note that information and action are the smallest particles we can observe directly.

A foundational constraint that we often acknowledge and account for in design is “human factors,” or the realities of the human body and cognition that impact how people are able to interact with an object. These principles, which have been variously documented by standards bodies⁷ and design practitioners (myself included), often appear at the bottom of a layer cake of considerations in discussions of interface design, but in a model organized from the principles of information and action, human factors are more like the shape of the cake itself. In the future presented here, individual intent would be a human factor that – just like touch, voice, vision, hearing, and cognition – we must be able to account for in the things we create, without precise knowledge of what it is or how it might change.

In other words: if information and action are the primitives that grow, seedlike, into the full flower of an interface, how people choose – and are able – to interact with technology at that interface is a superseding layer, and that is where true adaptation really lives.

✧

Bringing Interface into Design Space

One successful implementation of design based on this type of intentionality is the accelerating development of variable type technologies, fonts that are not packaged as individual styles as foundries have for hundreds of years now, but rather as one program that constitutes a continuum of possible expressions of a typeface. The product of the design process for a variable typeface does not presume to know or understand the intent of the creators who will work with it later – graphic designers and typographers are constrained only by which variables (axes) are made available within the typeface.

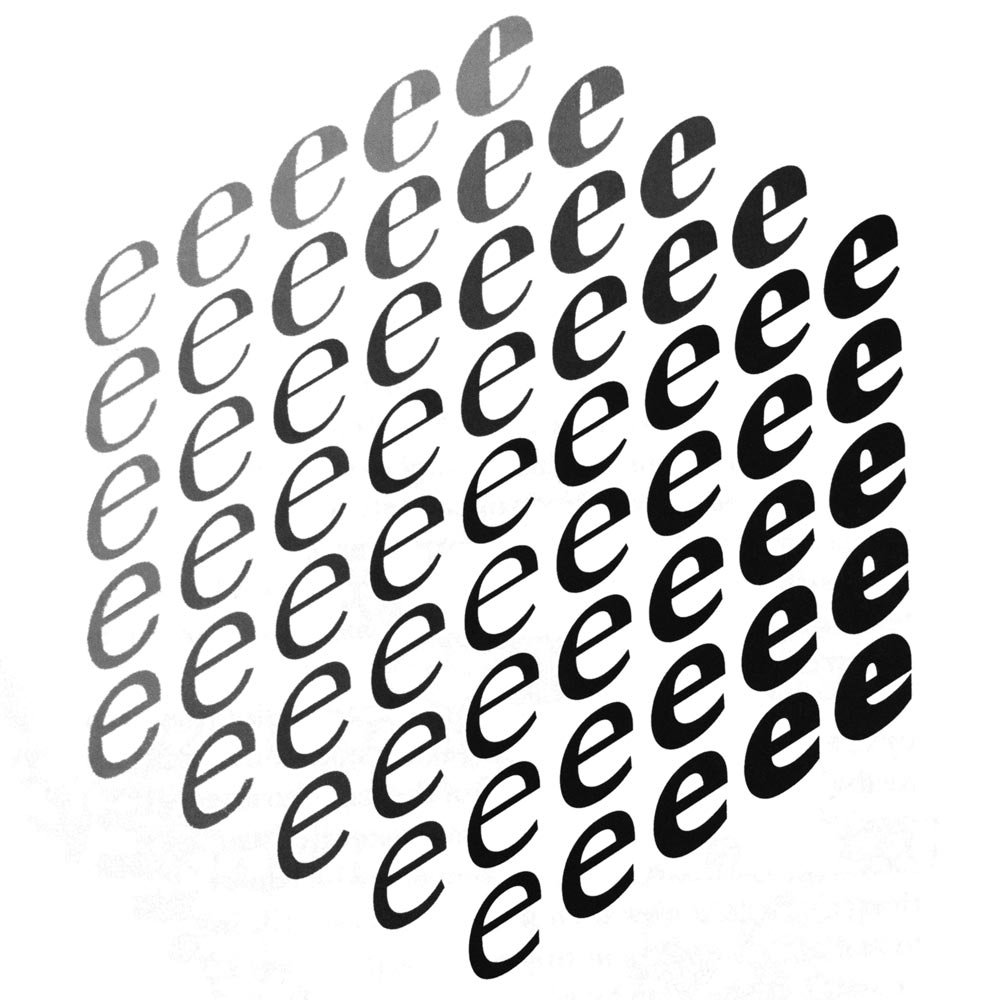

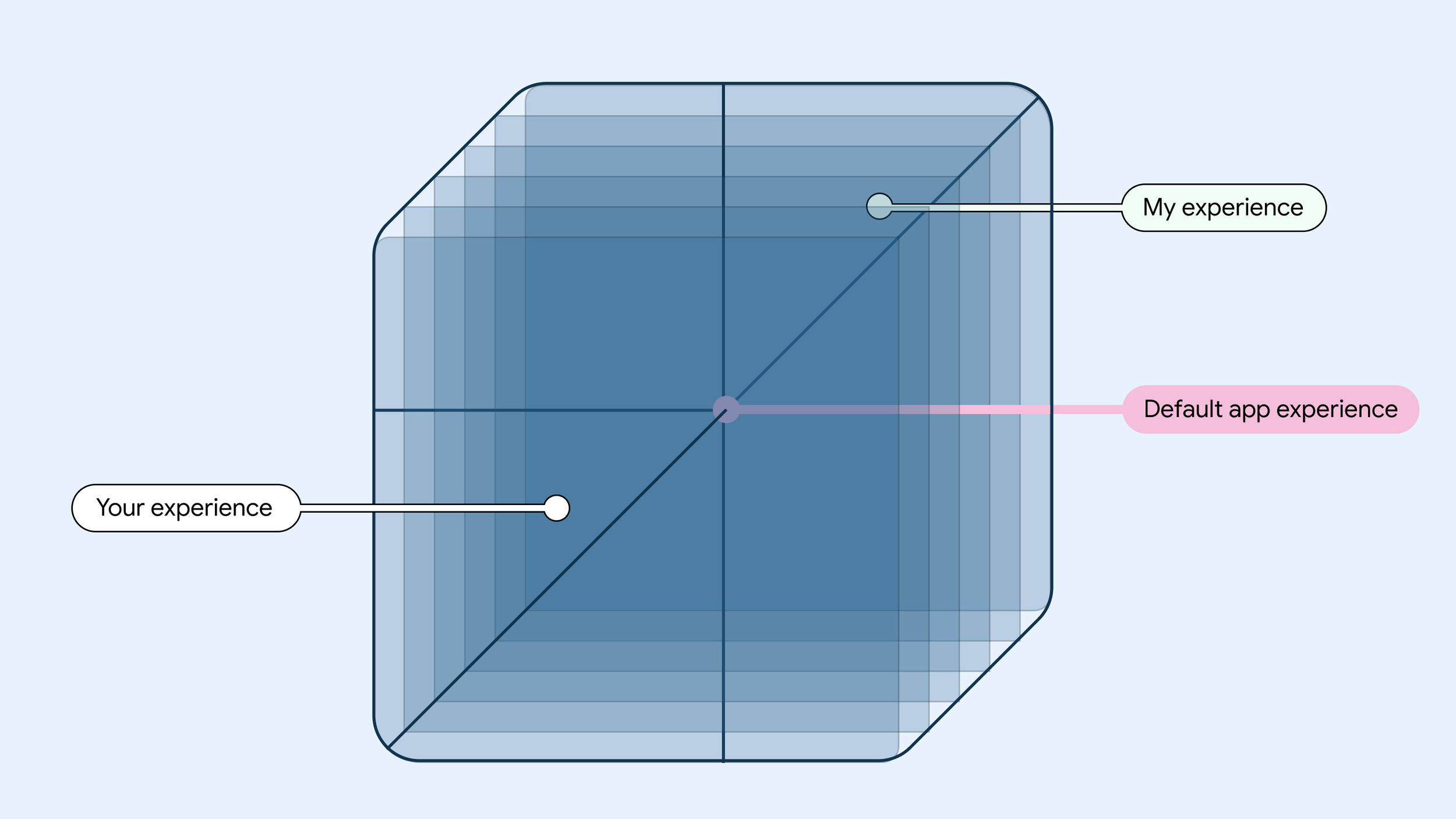

The Noordzij Cube (tdc.org) illustrates a 3-dimensional design space using the letter e.

When I studied in the Type @ Cooper program in New York, I learned from type designer Hannes Famira that a “font,” the instance of the typeface we were designing in class, was just once point in a multi-dimensional field called the “design space.” The variables in variable type, called “axes,” run through this design space like overlapping train tracks. Anywhere there’s an axis, we can see a continual line of expression through the design space. Some axes, like “weight,” run straightforwardly from one point to another – for example from thin to extrabold. Others intersect one another, drawing themselves into two dimensions. Others go on to become more complex, even having influences on several other axes as they progress through their own scale.

Project Phoebe saw digital interfaces as existing within their own kind of design space, where axes like touch or visual acuity, age, and others could all influence the instance of the interface a person is presented with. And today, we actually do have a few ways of instantiating somewhat complex axes in our work.

The Near-term Approach

A simple example to start with is adaptation across screens. In Material Design, we’ve created guidance for adapting to screens from large to small. The screens or breakpoints we document could be understood to represent individual stops on one axis – screen size – running through the design space.

But if we look more closely, it becomes easier to see moments where other axes may be running parallel nearby, or intersecting with screen size in interesting ways that we must account for. For example, on a very large or small screen, we can make certain assumptions about the device to which it belongs. A screen that’s TV-size might actually be a TV. This is information we have access to when creating an interface. What, then, might be the other axes lying just to the left or right, or overlapping with its screen size?

Design guidance for TVs specifically draws focus to things like attentiveness. We can draw from research and experience a rough knowledge of how attentive one is when watching TV and create an interface that matches that attention with the right level of detail, size of components, and types of information.

The way we organize actions around that information could comprise another axis having to do with input modality. On a TV, you’re likely using a remote control, gamepad, or other input device, rather than directly making contact with the screen. These possible modalities represent stops along this other axis, and this axis will inform how the interface is ordered in your app – how quick is it to traverse from one item to the next, or to reach a desired item from the top of the screen?

Interface design also exists in its own design space.

The natural direction of this line of thinking is to fully realize these and other axes for each app – and, eventually, an entire system – in a multidimensional design space, allowing an interface to function as one piece of technology that contains within it a fuller range of possible expressions, directly informed by individual intention; the person using the interface could determine where they land in the design space through their preferences, actions, usage, and implicit cues.

Dynamically themed imagery from m3.material.io.

Material You, introduced in Android 12, is one small step in this direction, opening up the system to an unknowable form of intent (user-selected wallpaper) which it uses to inform fundamental qualities of the interface (color schemes). In this case, the axis of color expression is populated by the HCT color space, which was created specifically for accommodating unknown user intent with perceptually consistent responses.

Visualization of the HCT color space.

There is, of course, much more work to be done if we want to realize a fully adaptive future at a system level, whether we’re talking about a design system or an operating system. (And I think we have to talk about both.)

Designing for Intent

In the more distant future, I believe that the interfaces we encounter on personal devices will be much closer to a pure flow of information and action rather than being deliberately and carefully grown from primitives to entire flows and apps.

The interface will likely exist in a framework that allows it to spontaneously arise and conform itself to emergent patterns based on the intent and subjectivity of the person using the device. The interface is, in this model, still the site of our encounter with technology. But the dynamic between object and subject (the chair designed for humans having material impacts on the humans that use it, the virtual couture designer encountering himself in virtual space) will shift, and we will see our own intent directly shaping the interface with which we’re presented.

This future would realize the promise of unwinding the designer’s intentions for the user – their behavior, their actions, their outcomes – and reconfigure the relationship, transforming it into one where the intention of digital production is simply to fit into the human environment seamlessly. The problem is no longer how to engage the user in an app, it’s how to unlock a specific possibility to the people who want or need it, using information and action.

Project Phoebe described an intermediate adaptive model that augmented existing approaches to create something responsive to invisible cues. A lack of touch acuity, for example, could be detected by nesting touch targets around a button; this was an existing technical implementation augmented for an existing component to become more than what it is.

Under a model whose interface is comprised solely (or at least mostly) of action and information, the design space discussed before could keep its axes while the visual and spacial presentation of actions and information becomes simpler and more modular.

New Deliverables

Our focus as designers, then, would be less on designing screens, flows or features, instead shifting toward meeting intents through organic composition. Our job as designers would then be to ensure that actions are presented according to information that matches the intent of the person using the interface.

We would find ourselves establishing anchor points within a multidimensional design space, determining the basic variables and boundaries that would ensure smooth gradation between regions of the design space which, in more concrete terms, would result in interfaces that remain familiar and usable and preserve the user’s mental model, but which adapt in similar ways to those described in Project Phoebe: individual actions that we might now call components would shift, adapt, and reconfigure themselves within a dynamically orchestrated layout, capable of composing and recomposing itself both in immediate response to state-changes and in longer-term progressive changes.

Design’s Responsibility

By this point it’s clear that changing the way we understand and practice our discipline will be complex. It will rely on new technology, experimental thinking, expanded resources, new tools, and a theory of design practice that reckons with our own position in the world as designers and the influence we have on how the world is experienced. In an interview for Design Notes, Senior UX Design Manager and former MoMA Design Director Rob Giampietro underscored the gravity of our work that I think makes this new model imperative:

It’s such a privilege to get to make the interface for the world. You’re deciding when someone should turn the page, how heavy their phone is that they pick up every day, whether they need to swipe to get more information or can have it right on the screen. All of those things are ways that you’re actually changing someone’s experience of their life through design. And I don’t think there could be a more transformative discipline than that.⁸

“Transformative” is an apt word here: When we design something, implement it, and put it into the world, we are causing transformation. At the surface level, we’re transforming someone’s experience of their life - that’s big enough. But we’re also transforming, potentially constraining, the range of possible experiences in the world by making choices about what a product can do and how it can do it. And we’re transforming ourselves; our discipline often puts us - our perspectives, our experiences, our beliefs - into the world within the products we create, just by virtue of the fact that we are humans creating things for other humans.

In other words, we are unavoidably present in our work. That goes for anyone who creates anything. The lives we have led until the point that we make an intentional creative choice will inform the outcome of that choice, no matter how hard we resist. This makes design a political and social action, and places a large amount of abstract – and, often enough in our industry, tangible – capital in the hands of relatively few people.

The only way to unwind some of the power we have assumed as designers is to build a process that deliberately dismantles it, putting the people we now call “users” in a better position to make their own choices, build their own experiences, work toward their own intrinsic incentives; a process that allows us to give up the notion that those things ever belonged to us to begin with.

1 “‘Gravity Falls’ Boyz Crazy.” IMDb, IMDb.com, 19 Apr. 2013, https://www.imdb.com/title/tt2813658/.

(It’s worth considering that this gif was clipped from an episode of the show Gravity Falls in which the men pictured are revealed to be imprisoned clones.)

2 “Keynote: Keller Easterling and Geoff Manaugh in Conversation (Span NYC 2015).” Google Design, YouTube, 6 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=bBdJSLSS550.

3 “TALK: The Interface (SPAN NYC 2015).” Google Design, YouTube, 6 Nov. 2015, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=wa7c_LrsWbo.

4 Barry Bergdoll. Marcel Breuer Bauhaus Tradition, Brutalist Invention, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, New York, 2016, http://resources.metmuseum.org/resources/metpublications/pdf/Marcel_Breuer_Bauhaus_Tradition_Brutalist_Invention.pdf.

5 Spradlin, Liam, and Kerry Murphy. Design Notes, no. 37, 18 Feb. 2020, https://pod.link/designnotes/episode/34608799b5dbd2ae59adea29b4b3f5f4.

6 Boellstorff, Tom. Coming of Age in Second Life: An Anthropologist Explores the Virtually Human. Princeton Univ Press, 2015.

7 “Ergonomics of Human-System Interaction — Part 11: Usability: Definitions and Concepts.” ISO, ISO/TC 159/SC 4, Mar. 2018, https://www.iso.org/obp/ui/#iso:std:iso:9241:-11:ed-2:v1:en.

8 Spradlin, Liam, and Rob Giampietro. Design Notes, no. 25, 14 May 2019,

https://pod.link/designnotes/episode/53b13783a15dfb8556137f49b19e7e45.

Taking Care

…amorphous and ever-changing, but simultaneously suggesting of the morphology that is perceived by everyone else…

Sometime in the beginning of the pandemic—maybe in April or May, when life inside my one-bedroom apartment had become ritualized but I still didn’t have any clear ideas about how anything might end—I decided to venture into one of my aspirational shopping lists titled, simply, “Art,” and buy something I had saved there. I have several of these lists, full of things I like but either shouldn’t, can’t, or won’t spend the money to get. But buying something to put on the walls felt right. I ended up buying three prints from an artist I had followed for a long time.

After completing my purchase, I opened Adobe Illustrator. There, I plotted out how I might arrange the pieces on my wall. Would I put a small print on either side of the large one? Should one hang in a different room? I focused on the particulars. If I had to stay inside for a long time (the naivety of buying a 90-pack of gummy vitamins “to last me through quarantine” had been fully realized by now), it felt right to spend some of that time changing things in the ways that I could.

Eventually, the prints reached me. The artist included the three prints I ordered, along with two smaller pieces. The extra artworks were a gift, not just because I got more than I planned on, but because these unexpected additions meant I could return to planning and configuring the artworks with a fresh perspective and new constraints. After unpacking everything and weighting the prints, I was ready to open my .AI file again.

But there was one more thing included in the package. Tucked between the prints lay a postcard. It was simple: black ink on white paper, handwritten. On the back was a line-art drawing of a man wrapping his arms around himself. The points of his elbows were aligned with one another, centered below the curves of his shoulders. His self-embrace formed a giant heart. On the front, the card said, “take care of you, Liam,” I think. Or maybe, “take care of your Liam.” At face value, I appreciated the sentiment. Inside, I relished the potential of the card’s ambiguity. That ambiguity would become a refuge where I could hide, just for a moment, every time I saw the card hanging on my fridge.

The notion of telling someone to “take care” is thought-provoking in itself. The idea of taking care of anything suggests a level of agency over the object of your caretaking, as well as an understanding of its needs. It presupposes a relationship to the thing being taken care of in which you can actively look after it and perhaps intervene on its behalf. A type of agency that felt increasingly absent as the months dragged on inside my apartment.

Telling someone, “take care of yourself” (could the “you” on my card be a shorthand?) then turns that agency into something reflective, making you the object of your own caretaking. It asks you, with full knowledge of your own subjectivity, to exercise agency over yourself. What that actually means or entails is a personal matter, as it relies on your own understanding of yourself. But the speaker is also suggesting a confidence that you’re up for the task, or at least that they give you permission and encouragement to make and act on your own determination.

If the card indeed said, “take care of you, Liam,” it expands that sense of personal direction from the speaker with an invocation of my identity as a separate being, reaffirming who I am at the same time that it affirms my agency over myself, wishing me well in the ongoing task of looking after my own wellbeing, whatever that means - either to the speaker or to myself.

But what if the little squiggle after “you” is meaningful, and the card says, “take care of your Liam?” Strange as it may read, it’s a fair interpretation of the cursive. What would it mean to overlay on the meaning of the preceding messages a sense that “my” Liam is a discrete object of its own? That my Liam is, for example, distinct from the artist’s Liam, or the Liam of anyone I meet on the street? How about the Liam that belongs to any of my friends or family members? Their Liam-objects, on which they enact their own caring or other effects? Taking care of my Liam is a separate activity from taking care of all those other Liams. A profound intimacy is inherent in the task. My Liam is different, needs different things, and has thoughts and feelings inside it, and I am the only one who can really access it. My Liam is amorphous and ever-changing, but simultaneously suggesting of the morphology that is perceived by everyone else and captured as their own Liam-object, a party favor taken home from every new social interaction.

Taking care of this Liam is a task much deeper and more nuanced than the demands of any of the other possibilities.

I indulge in considering the possibilities of the diction of this postcard because it came to me during the pandemic—a time of being alone, and a time of heightened awareness of myself and my wellbeing, and how rapidly both seemed to be shifting.

Interpreting this card’s message is like arranging and rearranging the art on my walls. The joy is not in arriving at any final or true image, but in the interpretation. It’s in the realization that the possibilities and in-between parts of the process are where fulfillment actually lies. That, regardless of what was written, or where the drawings hung on my walls, I could take for myself—from the process of deciding—the agency that was elsewhere missing. I could configure the words on this postcard over and over again, finding the version of the message that was most soothing when I needed soothing, most optimistic when I needed optimism, most kind when I needed kindness, and most thought-provoking when I needed something else to think about. And that, I think, is a way of taking care of my Liam.

Nebelmeer

A meaningful pause in the conversation between land and water.

Switzerland’s landscape is an eclectic mix of geological features acting out a constant dialogue between land and water. Traveling among mountains, through valleys, over rivers and lakes, one is given an object lesson in the forces that invite water to rise into the air, fall toward the earth, and flow in trickles and streams back to the ground. This topology imparts on the Swiss a network of highly localized cultures, linguistic practices, and climate conditions. On a given day, one could discuss the Schneefall – snowfall – in Zürich, the cielo soleggiato – sunny sky – in Lugano, and the forte pluie – heavy rain – in Geneva.

The country’s microclimates make weather apps an absolutely essential part of Swiss life. And a good weather app is one that has two primary qualities: first, up-to-the-minute accuracy. Second, a live map with clear iconography. Something I learned since moving to Switzerland is that – particularly in Winter months – knowing the state of various microclimates is crucial, and chasing the sun a sacred ritual.

Radio anchors, perhaps as an invocation to complement our holy tools, announce the altitude above which you can escape the fog each day. Enterprising travelers can then make their way up beyond the clouds and glimpse the secret sunlight inaccessible just a few kilometers away. There’s even a word for this: “Sonnetanken,” meaning to fill one’s tank with sunlight.

But ascending through the clouds to reach the sun is only half the fun, and not a fraction of the magic. Like the water constantly traversing the land, what goes up must eventually come down. Having gone up a mountain to escape the fog, you’ll be at the perfect vantage point to look down and see the same clouds stretch out around you in one hypnotizing expanse. A meaningful pause in the conversation. A space for your imagination to address the land and the water and their statements. The landscape flooded, the horizon indistinct as clouds meet the sky, you will begin to picture your descent into an ethereal, enveloping ocean inside the land-locked borders of Switzerland.

Design is Art After All

In the very same ways that art is not without design, I contend that design should not be without art.

When I paint … I look at it and I say, “The space in that corner there needs a little blue,” and so I put my blue up there and then, then I look over there and it looks blue over there so I take my brush and I move it over there and I make it blue over there, too.

This quote, and the surrounding passage from The Philosophy of Andy Warhol, has stuck with me for years. When I first read it, it seemed to hint at a sort of intuitive artistic power that I couldn’t access yet — a certain way of viewing your own work that allowed the work to exist in conversation with you as a creator.

In the full excerpt, Warhol describes his process of moving the blue paintbrush around the canvas until everything feels right, doing the same thing with the green brush, taking a look, and deciding when the painting was done. On face value this description might make it seem like a painting was thoughtless or unplanned, but I think the truth is that these paintings were embodiments of a sort of learned instinct for composing images.

And, like Warhol’s paintings, type design illuminates a powerful method of intuitive composition that can be applied across design disciplines.

Still from Shields’ lecture

As part of the Type@Cooper program, students can attend guest lectures in the Herb Lubalin lecture series (archived on Vimeo). During one such lecture about wood type, speaker David Shields diverted into Rob Roy Kelly’s book A Collector’s Guide to Trivets & Stands, which thoroughly catalogued the utilitarian objects. Shields mentioned that trivet design is actually quite typographic in nature. And I wondered what the possible connection could be, before realizing that maybe it was about the composition of the trivets.

Still from Shields’ lecture

The same way I’m learning to balance counter shapes with strokes to create cogent and readable letterforms, someone designing a trivet would seek to balance air with iron, creating a cogent and usable platform for a hot dish.

Back in our studio sessions every Tuesday, I would bring my latest design proofs up to Hannes Famira for critique and guidance on where to go next. Hannes can see things I can’t in the letters. He can pick out a control point from across the room, and see a “lumpy” contour with his eyes closed.

Halfway through the term, I was saddled with two interesting themes. On one hand, the idea that the compositional rules of type (beyond the orthodoxies of cap/lowercase proportions, serif construction, etc) could be broadly applied to other types of design and creation. On the other hand, the idea that there’s an advanced compositional sight and instinct possessed by experts — an instinct I couldn’t yet access.

And certainly this isn’t a new idea. “Be good at balancing compositions” is not a groundbreaking development. But instead of simply saying “knowing how to compose is important,” I want to take both of these ideas, open them up, and integrate them into the practice of designing interfaces — the thing I’m best at, and to which I tend to relate every new idea.

What isn’t design?

In a recent interview I said something that I’ve thought for a long time but never said openly — all things that are created are art.

What I mean by this, at least partially, is that there’s probably no point in spending mental energy sorting things into columns of “art” and “not art.” I don’t want to say something is “not art” and then be on the hook for determining what is. But I also mean to say that we should think more about things as intentional creations that have their own intrinsic meaning and that communicate something from the creator to the person encountering them.

Yes, this means I think the Venn diagram of art and design is basically a circle.

The unspoken second half of this statement is that all things created with intention are designed. Yes, this means that I think art is designed and, yes, it also means I think the Venn diagram of art and design is basically a circle.

I think it’s tempting to think of art and design as entirely different concepts because design feels like it’s different—like it has different goals, different processes, and often a more systematic role in how products are made. In an episode of Design Notes that I recorded with Fictive Kin’s Cameron Koczon, he said the following:

…when I ran Brooklyn Beta, I saw a lot of attention on design and it became something that VCs were talking about, business leaders [saying], “you gotta have it. You gotta get yourself some design.” … “Design,” the word, is now everywhere. Good job the word “design.” But designers, the community — I don’t think they’re getting much from it and I don’t think that those of us on the receiving end of designed products are getting much from it.

Koczon’s point (which is fully detailed in An Important Time for Design) is that the idea of design, particularly in tech, became sacred, and — adding my own interpretation — that the word itself became a sort of empty container into which we could pack our own strongly-held beliefs and ideals, often about the things we want or hope for. The practical result of this, according to Koczon, was not an elevation of the designers creating these new sacred objects, just of the word and the idea of the practice.

I think understanding that perspective, and giving myself permission to step back from the narrative that design is somehow an elevated mode of operation, allowed me to see that perhaps there was room to challenge other orthodoxies of design in tech, or at least to introduce new ideas to the conversation.

I already want to challenge our conception of interfaces as static or terminal creations by allowing them to live with users, but maybe right now, in the present, while we’re still dealing with interfaces that don’t adapt at that level, we can let down our guard around the concept of what design is (it’s a lot of things) and start to borrow again from the intuitive practices of disciplines like type design to inform and invigorate our work.

Learning to intuit

Something I had to unlearn when I started learning type design was the instinct to rely on numbers. Stem widths and spacing metrics called to me as opportunities for a strong system. I should be able to figure out the right values and apply them evenly across every glyph, right? Wrong. So, so wrong.

Many elements of type design are created and adjusted optically, and while the notion of a system is strong in type, the system seems to act more as a collection of concepts than a collection of immutable components. Mapping the optics and systems I know from interface design to type design consistently creates conflict in the letterforms. And to break out of this instinct I had to learn to intuit. To do that, I needed a new perspective.

Negative is the new positive

In a weekend-long workshop about letter proportions lead by John Downer, I found that perspective. Downer told us something that really started to change how I viewed the things I was creating.

He said to think of letterforms not as discrete objects lying on a background, but rather forms constrained by—shaped by—the background. That the counters in and around the letters were really what we were shaping, not the letters themselves. We should clean up a pool of ink, not create one.

And this stuck with me. Not just because it had a major impact on how I understand spacing in type, or how I perceive letters in relationship to the background and to each other, but because it also has broad applicability to interfaces.

One of the most common criticisms I read of contemporary interfaces, particularly on the web or large screens—but certainly with more fervor on smaller screens where space is precious—is that there’s too much white space. This negative space is often called “wasted,” or “unused,” or “empty,” but if we look at it the way Downer sees type, we can evaluate whether white space and wasted space are truly the same thing. And I think the answer might be surprising.

Negative space gives form and meaning to the positive space it contains

Negative space, at its best, gives form and meaning to the positive space it contains. Viewing it this way, we can give that space specific Gestalt duties — it can create or eliminate proximity, continuity, or closure. When negative space isn’t employed to these ends, you feel it. The interface, the typeface—the design—doesn’t quite work. More than a simple exchange of screen space-for-information, we should think about and evaluate use of space on these qualitative terms.

A collection of concepts

I’m not someone who likes to say “the best ___ I know do ___,” so indulge me when I say that the best design systems I know aren’t restrictive.

One of the major criticisms of interface design’s current systematic renaissance is that the design systems we create and share are too restrictive for designers, stifling of expression, extension, and the intuition I want to advocate for in this post. This was certainly a sentiment we heard about the early iterations of Material Design at Google. And to that end, Material has evolved. In 2018, the notion of Material Theming imbued the system with a broad set of subsystems and parameters that allow designers to maintain the fundamental concepts and usability of Material while creating a unique and expressive system.

A baseline 4dp corner radius, for example, does not mean that all shaped components will have 4dp corners — corners can vary based on things like the size of a component, its relative importance in the interface, or even the action a user is taking at the moment when they encounter it. They can be modified and made asymmetric to couch or emphasize actions. The shape system in Material has solid internal logic, but maintains a strong degree of expressive range.

When I designed Wakehurst, it came out more like a fern in a greenhouse than one in the woods.

And the internal logic of a typeface works the same way. Rather than having a set menu of components that we brick together into a whole, elements can be extended, explored, and redefined to form a cohesive but dynamic family of shapes.

When I designed Wakehurst (the typeface pictured above), I interpreted my reference text with organic, leafy terminals that evoked the growth of a fern, but that were contained in a rational, structured set of glyphs. It came out more like a fern in a greenhouse than one in the woods, growing organically inside a rigid structure rather than existing among other organic forms. Looking at the top of the a as it relates to the j, the y, the &, the c, and other characters you can see the variation.

A typeface’s system, in other words, functions as a slightly looser conceptual theme. A related but biologically distinct group of plants took root in Wakehurst, and can also take root in your design system.

In interface design, these new botanic specimens often spring up in response to new or changing needs or environments. Different soil, different rainfall and sunlight. Perhaps a foraging creature has come along and nibbled on your button components. Have I pushed this metaphor too far?

Extension, exploration, and evolution are critical to a system’s longevity.

Allow design to express itself

If we return to Material Design, and think about it in the context of a large organization where a given theme may be propagated to various teams of designers for implementation in their own specific products, it’s easy to see how even this highly expressive and stylized version of Material we’ve created can begin to feel claustrophobic. When confronted with an exhaustive stickersheet like the one generated by Material Theme Editor, it’s easy to perceive highly expanded choice as a set of boundaries.

I would offer that, in fact, this breadth of stylized components provides the minimum ingredients necessary to create a diverse and expressive range of products using the same theme. I know this because we’ve put it into practice with Google Material, the theme my colleagues at Google created to help give Google apps the richly expressive properties of theming and bring the Google brand to life across products and platforms.

Google News, Google Home, and Gmail

Functioning like many design systems, Google Material has its set of components as well as a set of principles and guidelines for the type of extension, expression, and evolution discussed earlier. And while the sorts of components and interactions the system provides are highly expressive of a very specific brand, teams have done a brilliant job of bringing apps like Google Home, Tasks, Calendar, Keep, and Gmail to life with Google Material in a way that still allows each to maintain a core personality and experience.

In the same way that Wakehurst uses stroke terminals to delineate different types of glyphs—for instance lending leafy edges to the $ to differentiate it from the S—carefully selecting, composing, and extending components of a bounded system can create interesting and dynamic personalities for related interfaces.

Harnessing intuition

The truth is that—as humans—we all bring something with us to the design process. The accumulation of our experiences, interactions, tastes, beliefs, and biases, are all revealed in our work. The things we create are naturally extensions of ourselves. And while it’s important to be able to emotionally detach from our work, it’s impossible not to see in it our own reflection.

Intuitive composition can feel volatile.

As an engineer, writing code to accomplish the same task on two different days will probably yield different code. As a type designer, I manage files carefully because I could never make exactly the same precise optical curve adjustments twice.

Intuitive composition can feel volatile. The lack of exact, infallible rules feels like a risk.

The key is to use intuitive powers with intent.

That our work naturally lends itself to containing pieces of our individual lives is — first and foremost — why it’s important to work with other people across a wide range of perspectives, backgrounds, and experiences as a designer. But it’s also why harnessing the things that make up our instincts and intuition is crucial to creating an intuitive composition that remains compassionate, thoughtful, and of course usable.

The key is to use these intuitive powers with intent.

Warhol’s make-it-blue-over-there painting technique functioned with the intent of balancing a composition for mass production.

Viewing typographic glyphs not as solid objects but as shapes bounded by the spaces they occupy functions with the intent of creating readable, comprehensible text.

Shaping components by their size, elevation, and importance functions with the intent of building strong mental models for a complex interface.

The goals of these examples may be different, but the process, the human qualities of the systems at work, and the instincts we build around that, are more similar than we may acknowledge.

So in the very same ways that art is not without design, I close by contending that design should not be without art.