Design Notes

Design Notes is a show about creative work and what it teaches us. Each episode, we talk with people from unique creative fields to discover what inspires and unites us in our practice.

Judith Donath, Founder, MIT Sociable Media Group

Exploring potential futures for life online and the joy of learning (and sharing) something new.

Exploring potential futures for life online and the joy of learning (and sharing) something new

Liam speaks with Judith Donath, the founder of MIT’s Sociable Media Group, inventor of e-cards, and author of The Social Machine: Designs for Living Online. Donath’s work offers crucial insights into the sociality of digital products and platforms, and the opportunities we have as digital producers to make things that truly meet sociable ends. In the episode, Donath unpacks some of this work, exploring potential futures for life online and the joy of learning (and sharing) something new.

Liam Spradlin: All right, Judith, welcome to Design Notes.

Judith Donath: Hello. Happy to be here.

Liam: So, just by way of introduction, as usual, I want to ask you to tell me a little bit about your work and the journey that's led you there so far.

Judith: Wait. Where do you want me to start?

Liam: The beginning. (laughs)

Judith: Well, where I am right now is I am in the midst of writing a book about technology and deception. But the way I got here was a fairly roundabout way. My undergraduate degree was actually in history. And I was really interested in medieval history and early scientific revolutions. But in looking at how scientific revolutions change society, I got, I, you know, this is in the '80s. And I was thinking, you know, I could take computer classes. There's a whole technological revolution going on now. I could see what it's like on the inside. And I took one class and was completely hooked.

I loved programming. It was taught in APL, which was a language that used mostly just Greek characters to program, and everything is in the form of matrices. And it just seemed like this really fascinating way of thinking where you just are trying to model something, but you're turning everything into a series of matrices. And then, I learned Lisp, and it was turning everything into linked lists, and, you know, got really, really interested in programming. I had also been doing a lot of work in film.

And anyhow, this is how I eventually ended up working as a game designer, and then went to the Media Lab with its first opening. And was, uh, you know, because my background was considerably less technical than most people who are coming in from computer science, especially at that time, I had a background in history and film and art, um, my work, you know, from the very beginning, leaned towards looking at what sort of the humanistic side of computing was, really interested in what was going to happen when people could use computers to communicate, um, things like the, you know, early email, what it would be like to have a whole society connected. And that's the work I continued to do for quite a while.

Eventually, I stayed on at the lab, and I ran a research group called the Social Media Group, where we looked at the question of, you know, what, what is it, what does it mean to be in a social space online? And in particular, how do people get a sense of other's identity? What are the ways you pick up from these, like, very sparse queues? Now, those queues online are sparse, but one of the things you don't really think about is how sparse in many ways the queues are in everyday life.

The example I'd often use with my students was, what can we do to make an experience like sitting in an outdoor cafe, and just watching the world go by? People walk past, and you might be wrong, but you have a very strong impression of a lot of people of what their politics are, what their personality is, and it's based on like a fleeting glimpse of them. How does that work? And what would it mean to transform that in a world that we have so much more control over how it's designed? And so, we did a lot of work with visualization.

One of the things that I drew from my film background was, in film, you kind of break down, uh, you know, one of the ways of categorizing shots is long shots, medium shots and close-ups, where long shot gives you like this whole establishment of a big scene of the world, the whole setting, and environment. And medium shot is really about the relationship among a small group of people. It's, it's how you shoot a conversation. It's about reactions and how people are interacting with each other. And a close-up is really like a portrait where you're really looking at a specific individual.

And a lot of what we were interested in doing was thinking about how we could make online interfaces that both address those three different scales, but also would be able to kind of move smoothly between them. Needless to say, if you've looked at Facebook or Twitter, we're not quite there yet, um, in the actual world with real life living interfaces. But I think those sort of general problems are still a very useful way to think about it. And, in particular, now, with all the hype, I don't know there's excitement, but there's certainly a lot of hype, around the metaverse, um, that question of, of representation, and what is it you want to see of others, and how you structure that space should be at the forefront.

And one of the things that I think is very disappointing about the ways I've seen any of this imagined by the people who claim to be building it is that, they've kind of alighted that problem by basically saying, well, it's gonna kind of look like real life. Here's a picture. It's kind of cartoony, but we're all sitting in this kind of tedious looking meeting room. Like-

Liam: Right.

Judith: There's really no reason why you should wanna make that be your representation for an enormous number of reasons.

Liam: Right. I, I wanted to get into that a little bit, because as you're talking, it strikes me that, you know, you have a background in film, which is kind of representation of reality that's like attempting to capture some, something that it must exist in analog space, right?

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And then also working with virtual space, which, although it is created digitally, can represent almost anything. And I'm curious how you think about that, like the different ways of representing a type of reality that are available to us?

Judith: Well, one thing about film though is that, I think fairly early on, the practitioners were interested in getting away from that sort of pure reality, if, you know-

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Judith: It was one of the most avant-garde films or filmmakers was Andy Warhol, who just took a camera and turned it on for eight hours. That's a representation of reality. But it's both unwatchable, a very avant-garde, that it, it turned out that a lot of the way of creating a story with film was through doing things that have nothing to do with what we see in real life, all kinds of things about cutting, you know, how you cut films, how you make reaction. It doesn't necessarily have this analog to virtual space, but it was certainly very imaginative in trying to understand how you create something that is a time-based medium and has starts with a recording. But a lot of what makes film is the way it's cut, the, the pieces that are taken out of it.

Now, in terms of thinking about how we look at virtual spaces, you know, I think the, the problem is quite different, because ideally, we're not filming. But what we want to think about is, how do we represent in a visual sense the information about a person. So, I think, you know, a cartoon of someone is not gonna be that interesting, certainly be less interesting than looking at them face to face. But what is interesting is that you have all this history of interactions. And you have, how someone ha- like what someone has said, you have their words, you have, you might have who they follow. You have all these other pieces from which to build a representation from.

And I think that's the really interesting challenge. And it's not really been followed very much. There's, uh, a paper by, uh, Jim Hollan, and Will Stornetta, which is quite old at this point, but they had a line in it that's, uh, for me, has always resonated, which was saying that you, it's called, the paper's called Beyond Being There. And it's a challenge for designing social interfaces to say, we don't want to recreate reality. We want to do something that's beyond it. And it doesn't necessarily mean it has more detail or more pixels or more dimensions to it. Often, it's the removal of those things.

There's reasons why a lot of online forums that are text based are really interesting. It's not that they're missing a huge visual component. It's that you can do all kinds of things when in the interface, when you, you could thread things, you can move stuff around. So, it might be quite minimal, but it's not about representing the look of reality. It's about representing the relationships that you're developing in your virtual reality.

Liam: There is also something you said about film being a time-based medium that really stood out to me.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And now I'm thinking about how that applies to the other things that we're talking about, like a forum, for instance. I would suggest maybe less time based in the sense that people say things, and then you can refer back to what they said after a time where, in real life, you might have forgotten about it.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And I wonder how that factors in to how you think about creating other virtual spaces.

Judith: Right. Well, yeah, one of the things we explored, it wasn't a dead end, but it was a place where there's lots of exploration still to do, is thinking about, for instance, those forums where stuff has been built up over time, how do you rep- you know, what's an, uh, much more interesting way of representing that sort of agglutinization of how things pile up over time. Or even something like I'm, you know, as I'm writing a book, I spent an enormous amount of time in Google Scholar, which is not something you normally think of as a social interface.

But if you think about the way that papers have citations in them, and those cite other things, and some, some papers become really popular, or they become really controversial, and there's, you know, if you could map that, which you can, you just happen to, but by mapping that, you would have a really interesting space to explore. You could see what's been influential. You could perhaps prevent people from doing the same thing over and over and over, because they're simply unaware of what they're building upon.

And even in forums, there are times you may want to do that, particularly in certain advice forums. I think it's a interesting design problem, both how do you extract the information about what is the interesting material, how do you map it, but also, how do you know when that's a useful thing to do, because sometimes with something like Wikipedia, you want to develop this encyclopedia of knowledge. But sometimes with a forum, the point is for each person to be able to go in and talk to other beginners or people at intermediate levels, or people want to teach. So, by making it all a reference site, you might lose that. So, it's, it's also about being thoughtful about whether where you're looking for the experience of the interaction versus the experience of being able to look up the information.

Liam: I'm really interested in this idea that the representation of you that exists in these spaces can be something like an assemblage of information, and maybe also visuals, but, but-

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... also primarily information. I want to dig more into that, like the concept of being embodied, virtually, and how many shapes that can take.

Judith: Mm-hmm. Yeah. So, you know, uh, again, I think this is a, uh, still a research problem and something that for a variety of reasons is not part of our current interfaces. But let's use Twitter as an example, because it's pretty simple. And it, but it's also one of the places I feel need something like this the most, because you're quite likely to encounter people who you have no idea who they are, or if they are a person, or are they, you know, are they a bot? Are they someone who's just come in as a provocateur?

So, if you could see people very easily as a representation that, you know, would still be like a avatar, something you could see at a glance. But instead of being a drawing, it was a visualization that showed you something about their history online. Is this someone who's been posting for years? Or did this account appear a week ago? What are the words and phrases that show up a lot in their history? How has that changed over time? How many followers do they have? And can we have a little representation of what sort of things do those people talk about? And who is it that they follow? Yeah, when a service like you could be like a set of word clouds type of thing, but something like that that would give you, at a glance, a way of starting to get a vivid impression of who they are in a way that's relevant for that space.

Liam: One thing that stands out to me is a connection to a piece of discourse that I think I encounter often about social media, which is that it is perhaps presenting us with too much information or information that is like too disparate, and yet drawn together, that it becomes overwhelming for us to handle.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And I wonder how such an embodiment would interact with that, if it is even a valid idea. And the second thing is how we would come to understand our own embodiment in that context, whether or not we could actually modify or manipulated after the fact.

Judith: Mm-hmm. Well, I mean, in terms of sort of quantities of information, again, that's a design issue. So, you could think of it this way. All of these things can exist at, at multiple scales, where there would be something that you would just see at a glance, and it would be sort of like the avatar that sits by this, this side, but instead would at least give you that basic information, like how long has this person been online, you know, a quick visual presentation of, you know, how much do they post, how long would've they been posting, how many followers do they have, how many people do they follow. So, that could be just a very straightforward, simple, almost stick figure scale piece. But then you could have, you know, like a simple slider-like thing that just starts to drill, you know, if you s- are curious, you could just see a more and more detailed version of it as you, you know, if you're like, oh, I want to see more of this.

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Judith: You don't have to have like a huge pile of information. But that's, you know, that's not a complicated design question. The question of what your editing abilities are of that past, that's really, I would say, application specific, and that's part of what makes the different environments that we go to, because there are some, there may be some spaces that are about saying, conversations here are ephemeral, you know. You say some things, they're here for a day, and then they're gone. Other spaces may be about saying, you say this is like the congressional record. It is never gonna go away and it's gonna be here for life, and you can't change it.

And there's others that's, you know, they could say, well, you have this. You can delete things. Maybe you can't add things. Those are all like, you know, in a way of thinking about it is that this platform is a little bit like going to different restaurants, you know. It's not that a fancy French restaurant is better than McDonald's. It is in certain things, but not if you're taking six, six-year-olds out to dinner, you know.

Liam: Right.

Judith: That you really want something with plastic surfaces that you can clean really easily. So, you know, all those questions about history really change the tenor of the social experience. But I think in a more ideal world, we'd have more platforms and more spaces, and an easier ability to choose among those. You know, it would be the sort of thing people could choose, you know, even at the level of their own page or their own, you know, if I post this, I'm gonna start a discussion. Now, I'm the host of the discussion.

And I can change the parameters for it in a way that's clear to the people participating in a richer way. I think things like that would, as people became used to it, would I think help us be able to create the types of conversations we want over different ideas, the same as we now know you can invite someone for coffee is very different than saying, I need to speak to you in my office right now.

Liam: Right. (laughs) Or sending, sending a text that says we need to talk.

Judith: Yeah.

Liam: I'm wondering. Being able to do all of this in a digital or virtual environment makes it perhaps a lot faster or easier compared to actual life where, you know, if you invite someone to coffee, you need to actually probably physically go to the coffee place and agree on where that is, and how to get there-

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... and everything. Whereas, maybe you could do more of those things faster on a larger scale, digitally.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And I'm curious what that means for how this form of interaction contributes to our personhood or our understanding of ourselves.

Judith: Yeah. I think, well, for one, this is a huge revolution we have lived through in our time. You know, it's actually very quickly that we've kind of forgotten how revolutionary it is. I mean, there's a paper called something like Mass Conversation, and it's from the '80s or early '90s. And, but it's like basically saying, like, hey, you know, we're having conversations with 50 or 100 people. This is just unprecedented. And it became a pretty much something we, we got used to that you would go online and, and just be in some conversation with enormous number of people.

But, so, there's a couple of, there's a number of interesting ramifications about that. One is that these conversations are also very lightweight. There's very little commitment, in particular, the fact that you are not physically present and that in many situations, your identity is either easily obscured or effectively irrelevant. If people don't know who you are, they may get to know your real name. But in general, that may not make a huge difference. So, the lightweightness tends to make it so that people feel that there's very little consequence, and there's cer- certainly a lot less meaning to it.

The, you know what you said about the effort that goes into even just having a coffee, but that effort gives it us, the experience a certain significance that we lose here. We have this bigger scale, so we have a much larger scale of less significant interactions. So, that's one big change. And then, there's the whole question of how are people drawn together. It also means that we've lost the significance of geography in a lot of ways. The fact of, you know, we ha- we're able to do this easily. You're on the West Coast. I'm on the East Coast.

People can talk all over the world. But it may mean that we lose track of what cultural differences may underlie a lot of the conversation which, when you're speaking face to face, whether it's that you, uh, have an easier time noticing that there's all kinds of cultural behaviors that remind you that you may only share a certain number of assumptions with the people around you, all get kind of flattened online. So, what we're dealing with is a world where everything is a little bit cheaper, but there's much more of it. And-

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Judith: You know, I think that goes hand in hand with a lot of other social changes, some of which are separate from the internet. There's at a much larger scale where we are less dependent on other people. If you look at, if you read stories of like, life in 1800, where you might need your neighbors to help you with the harvest, or help you repair your house or raise your house, you need pretty significant committed relationships to live in a world like that. The internet has come, you know, probably not coincidentally, at a time when we were already moving a lot of the things we need other people for to a market.

Like I don't have to rely on family to have babysitters. I can hire someone. You know, I can hire a stranger. There's a, you know, I'm not asking someone to help me harvest my food. In fact, I'm just buying it at the supermarket. So, we have this opportunity to have all these relationships and conversations in this very lightweight way at a time when we are already kind of in the fading days of certain types of very expensive, in terms of time and effort and reliance on relationships.

Liam: What do you think are the most pressing design challenges in the space right now?

Judith: There's some huge pressing issues in the world that are somewhat conversation based. And a lot of that is around misinformation and, um, our inability to deal with diversity, and the, you know, sort of the growing hostility between political camps both in the United States and worldwide. So, those are, are worldwide issues. They're very conversation based. They certainly have representation online. So, I would say in, you know, in terms of pressing this, the question of how to get people to be able to converse and interact in a meaningful and useful way with people they do not agree with is probably the most pressing one. You know, it may not be the most exciting design challenge, but it's probably the most pressing issue we're dealing with.

Liam: I think that also speaks to the way in which the intent of designers, and software engineers too, for that matter, plays out in these conversational spaces or digital products. I'm thinking a lot about, you know, is the answer that as a discipline, we simply have to own up to that and come up with solutions to this problem? Or do we actually need to divest some of the power that we have taken in that in order for that to improve?

Judith: I think the, probably the most pressing problem, on the flip side, is that an enormous number of design decisions are made, not with the goal of how to make the best social space or how to solve these things, but they're made in terms of how do we satisfy advertisers. How do we get people, you know, how do we get people to stay online more? How do we get them to do these things? But they're, these are not social goals. And so, our interfaces are not being designed to make the social experience better. They're designed to make the extractive experience better.

Liam: Right.

Judith: And, and so, I think finding ways to have significant and heavily used sites that are designed for the social purposes. I mean, there's some, I think, pretty well known analyses that say, you know, certain things about how some conversational interfaces are made now or that effectively end up encouraging disputes, because to a simplistic assessment algorithm, it looks like engagement, you know.

Liam: Right.

Judith: You know, it might mean if you want to follow that path, your computational analyses of conversation needs to be more sophisticated, and not mistake argument for engagement. It may be that engagement isn't the right goal. It might be that trying to algorithmically prolong or shorten conversations isn't a really useful thing. Maybe let the actual people who are participating make that decision and don't really try and weigh on it in either direction.

Liam: Right.

Judith: When you spoke earlier about sort of this accumulation of information that we have in these discussions.

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Judith: So, the earliest discussion space, both I was familiar with, and, and then I did a lot of work analyzing was Usenet, which was just threaded topical discussions with sort of no algorithm, but very heavily text based. And it had a pretty rich culture, you know, and information would grow. And then, at some point, people would say, okay, well, we're tired of explaining, you know, how to, let's say it was a group on having like a home aquaria. You know, these are some basic things. We'll put it in a FAQ, and then we'll continue to have that discussion. And they would tell people, read that information, then join in the discussion.

But there was still a interesting, ongoing discussion, and there wasn't any index into it. There are multiple things that went into the demise of Usenet. But I think one of them was, at some point, Google bought up all the, or gathered up the archives of it and indexed it. And what happened then was that, instead of, when I wanted to learn something about a particular field, instead of what people had done, which was get to that news group and start reading it, become familiar with the people in the conversation, and then dive in, you could just make a query, and you would get an answer. And if that didn't answer it, then you just make another question.

But because you could dive into a whole index of the discussion, people stopped seeing it as a social space where they got to know the people and the participants, and then took part in it. They just sort of saw it as a encyclopedia you could query. And it changed the nature of it enough that that was, you know, well, it wasn't the only reason it stopped being a useful space. That was one of them. But that was certainly done with very, with good intention of making it more usable. But it had this fairly unexpected opposite effect.

Liam: Right. Yeah. It feels like it's coming from a place that I think many things in the tech industry come from, which is that data are the ultimate resource for understanding things.

Judith: Well, that and then what's a big theme in the book that I'm working on is that, a lot of technology is really designed to make things more efficient. But it turns out, a lot of things that are costly to do, those costs, and I mean in cost and energy, or time or effort, allow those costs to now to actually be really valuable in some way. You know, in that example, it was the cost of sort of reading through all these conversations. There are other costs that have to do with, you know, the commitment, the effort to make go for the coffee or the dinner.

And when you build technologies that make things more efficient, it's great when the effort that you've now eliminated really was kind of wasted effort. But it turns out like an awful lot of examples of the effort really weren't useless, uh, and particularly often serve some important social purpose, either in showing your commitment to someone or something, or making you more adept at something before you go on and try something else. And when you build tools that eliminate that, you've taken away something really valuable.

Liam: Right. You know, speaking of Usenet, I also want to talk about another case that is very dear to me from earlier in the internet's history that I think could be a really interesting conversation as we talk about, you know, the design challenges of relatively new modes of, of existing online. And that's e-cards.

Judith: Okay. (laughs)

Liam: I feel like the progression of e-cards could be a nice surface to map these ideas onto, especially as I think about, you know, my own history with the subject as starting in a time when email was really exciting.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: And I think in many ways, the internet, you know, still had a capacity for emulating some of these offline mental models. So, I was wondering if you could talk a little bit about that, because you're cited as the inventor of e-cards.

Judith: I am the inventor of e-cards. Well, I was procrastinating writing my thesis. (laughs) Yeah, that's, so, I'll tell you how I ended up doing it. And then I can talk a little bit about my thoughts on this.

Liam: Sure.

Judith: Uh, well, and I was working on my thesis, and so open to any kind of distraction that anyone wanted to present to me. And my office mate was, had gotten very, very excited about the computer language, Perl, and actually, you know, was writing the, one of the early textbooks on Perl and insisted I learn it. Uh, it's a language I still cannot stand. But I had done some consulting for a company. Uh, I, you know, some early internet company was trying to do some online travel thing. And I had suggested to them like, hey, if you're gonna do like travel, why don't you like have, like, postcards people could send from somewhere online? And they looked at me like I had six heads. It's like, yeah, no. Not interested in that idea at all.

So, and my office mate, this idea was floating around in my head when he said, you've got to learn Perl. I thought, well, I need to assign myself a problem. And that's how I will learn it. And I thought, well, why don't I try and do online postcards? How would that work? How would you send a postcard to someone? So, that was the genesis of it. It was not a deep research piece or anything. And so, I had lived, before I went to graduate school, I had lived in the East Village in the '80s, when it was still mostly burned out buildings and everything. And it was, (laughs) the postal workers there were very surly, a couple of times had found all our building's mail in the trash. (laughing)

And, um, so, I've modeled the postcard site, uh, off that sort of model of disgruntled postal worker. So, it's very cranky. And you would, basically, for those who haven't seen this, you would get an email. That's, you know, someone sent you a postcard. You get a email that said, you have a postcard waiting for you. Because one of the issues was the wa- uh, it's, also this is, another piece of this is that the web was very new. And there weren't that, there were almost no, pretty much no social applications on it. And so, for me, like coming from things like Usenet, the web was kind of cool. But it was also a little disappointing, because, you know, especially then it was just pages. There just wasn't a way to interact with others.

And so, trying to figure out how to put some form of interaction into it was part of the postcard challenge. And so, it had to be this kind of kludgy thing where you would get an email that told you to go to a page, and the page would then be rendered with a postcard for you. And I started it, you know, I think it was, I'm thinking 1994. And it came out right before Valentine's Day. And so, like there were a couple days, so, two postcards, sent three, seven, 10. And then, Valentine's Day hit, and that was in the hundreds, then it was in the thousands. And within a couple of months, it had taken down the network to the Media Lab, and I had to have, like, a special line run to my computer so that it wasn't taking down the entire net there, because it was so incredibly popular for about a year.

And so, one of the challenges, my adviser was like, wow, this is really amazing. You've done this really successful thing. You know, you know, this has to be a thesis. I'm like there just isn't a big there, there. It's online postcards. And so, I spent a fair amount of time. Usually, you have to write about this. Like, I'm like, well, what can I say about this? So, the sort of deepest insight I was ever able to extract from this project was that, when you write, you have this technology. People just, you know, this is still when, as you said, email was exciting. But one of the things is, when you write a email, you have to say something. And you often don't really have anything to say. And that's-

Liam: Yeah.

Judith: ... I think what people really liked about the postcards, because it became this way to just, it's a li- a little bit like a little present that you could send to someone. You know, there were all kinds of, I mean, part of it was I spent a lot of time gathering like a huge range of postcards, which I'll talk about in a second. But it was a way to reach out to someone and send them a note without actually having any reason or meaning. Like email is, is really something you, you know, you have to have some message. You can't just say hi and that's it. But you could send a postcard and just say hi.

And I think that's what people really wanted. And in, then, you know, if you think more deeply about it, if you look at things like social psychology, there's the concept of phatic, P-H-A-T-I-C, interaction, where it's the interactions we have, where there's not a lot of content in it. But they're really important for just sort of aligning people. If you look at, you know, if you run into like, uh, an acquaintance in the grocery store, the conversation may be completely empty. And people say, well, small talk, it's so useless.

But it's not. It, you know, how you use it, the fact that you, you know, even eng- you know, even engage in conversation with someone, says, okay, I acknowledge you, you know, if you remember a little bit about them, there's all kinds of social information in that. And what the postcards did was that let you have that type of interaction that email didn't. And I think that was its big social contribution.

Liam: Yeah. You know, I can't help but notice that it kind of created one of these types of, I guess, low resource interactions that we were talking-

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: ... about before that have become so prolific, and also that it was something that came from a social desire to meet social ends, and was hugely influential because of that.

Judith: Mm-hmm. And it also, some part of it was to let you just sort of reach out and touch someone in subtle way. And it was also that it let people say, I have found something new.

Liam: Mm-hmm.

Judith: And then send it to others, which people really liked to do now. Now, that's been so speeded up that it's, you know, a whole different expectation of what is new. But still, you know, I think at that time, there would be a few new things on the net. But this is, you know, this is even before, I think it's bef- you know, it's either the very early days of Google or before Google Search, where simply the problem of finding something new online was significant. How did you find things?

Liam: Yeah. And I also think it's like a very human impulse to want to demonstrate that you have some new knowledge.

Judith: Great. Something new, yeah. Exactly. Yeah.

Liam: Just in itself.

Judith: Mm-hmm.

Liam: I think that's a great thing to wrap us up with, Judith.

Judith: Okay.

Liam: Thank you so much-

Judith: Thank you.

Liam: ... for joining me.

Judith: This was really fun. You have great questions, and this has been really enjoyable.

Tom Boellstorff, Anthropologist, Coming of Age in Second Life

Anthropologist Tom Boellstorff on life—and the future—in virtual space.

Anthropologist Tom Boellstorff on life—and the future—in virtual space.

In this episode, Liam speaks to Tom Boellstorff, Anthropologist and UCI Professor, whose ethnographic work in Second Life (documented in his book, Coming of Age in Second Life) provides important insights into how virtual space – and our interface with it – informs and interacts with our lives in actual space.

In virtual worlds like Second Life, inhabitants exist only through their own acts of creation, which also serve as a primary mode of experiencing life in virtual space.

Liam Spradlin: Hi, Tom. Welcome to Design Notes.

Tom Boellstorff: Thank you for having me.

Liam: So to start out with, as is tradition on Design Notes, tell me a little bit about your work and specifically the journey that led you there.

Tom: Sure. I'm an anthropologist and I'm a professor at the University of California, Irvine. And I actually started out doing research in Indonesia many years ago about gay and lesbian Indonesians and sort of how identities move around the world on how they change and don't change when that happens. And I started doing that research in 1992. I started doing it a long time ago before the internet was even there. But when I was doing that research, I really saw the influence of mass media already, television and films and things like that. And that got me interested in technology and media.

And after doing that research for about, oh, 15 years in Indonesia, I thought, "Oh, I'll try something a little different." And so I had had that interest in technology and so got interested in virtual worlds. And this was in the early 2000s when they were just getting started and thought, "What would happen if I tried studying virtual worlds using the same approach that an anthropologist uses when they go to Indonesia or anywhere else, trying to understand a culture? How is it different or similar? How does it work?"

And so I sort of tried that out as an experiment and it worked really well and there you have it. And so for a while now I've been doing digital anthropology research about the internet. So I've been very lucky to have a career where I get to do all kinds of different stuff and I'm getting ready now to sort of come back to virtual worlds and do a research project on the anthropology of the metaverse, people are calling it nowadays, and looking at some things that are going on around that.

Liam: It's striking to me when you characterize your work before virtual worlds as exploring kind of the nature of identities and how those shift and change in different regions of the world, that studying a virtual world must kind of explode that concept.

Tom: It is interesting. Like in some ways it explodes it. But one thing that has always surprised me studying virtual worlds is that a lot of it isn't that different. And so seeing a film or a movie or getting an idea of a concept from somewhere else in the world and transforming it. Like in the case of Indonesia, which is the fourth biggest country in the world, that's been going on for hundreds, thousands of years. Indonesians are almost 90% Muslim and many of the others are Christian or Buddhist. Those all came from elsewhere. The idea of the nation state came from elsewhere, being a nation and so many ideas. And that happened in the US as well.

And so humans have always been very trans-local, like ideas and things have always flowed and moved. And sometimes that's because of people moving. But sometimes ideas can move when people don't. And that is something that with the virtual world kind of thing really gets transformed in really interesting ways. And one thing that is sort of exploded, or one thing that is truly different is the difference between an idea moving from one place to another physically, whether that be aided by radio or movies or internet, compared to an idea taking form in the internet itself. And that is something different because a movie or a book is really interesting, but we can't talk there together. But right now we're talking. And so there is something really cool that happens with the possibility for those kinds of virtual spaces, for sure, that's something that's really interesting to study.

Liam: I wanted to get into that more, but first I want to back up and just define a couple of terms as we get into this conversation. So first, how would you characterize a virtual world or virtuality in general?

Tom: Yeah, that's a really good point. So right now, especially in this sort of new era of metaverse hype that we're in, virtual gets used in two different ways that are actually very different. And so it's important to keep those separate but also look at areas where they overlap. So one is VR, virtual reality, which means the goggle kind of Oculus Rift thing where you see things in 3D and that's really cool, and whatever, the technology's improving.

But you can do VR without the internet at all. You could have a flight simulator on your computer, on your laptop, if it's not even plugged into the internet. So virtual reality is about an interface. It doesn't have anything to do with being online at all. You can do it, unplug your computer from the internet, turn off the Wi-Fi, and you could do VR with any kind of game that you're playing or a flight simulator or something. And so that's what virtual reality means.

Virtual worlds means a shared online place where this is a picture of my house in Second Life, one of my houses in Second Life, where if I shut off my computer and I come back the next day, it's still there because it's on the cloud. It's a shared place online. That's what a virtual world is. And that's different from a social network site. And we even see that in English where we say that you go on Facebook but you go in Minecraft or Fortnite or something like that, Second Life.

Many of the early virtual worlds were text-based. You don't even need VR. You don't even need graphics. They can just be text, where it would say, "Tom walks into a room. The room has three chairs and a table." And for instance, when some disabled folks with visual impairments use Second Life, they use readers that read it out as text. So even nowadays. So you can have VW, you can have a virtual world without VR and you can have VR without VW. One's about interface and one is about shared place. And so it's confusing because those are two pretty different meanings of the word virtual.

Now, part of the whole metaverse thing is the kind of Venn diagram where you can have a virtual world that uses VR. Super cool as long as you don't get nauseous or whatever. And so you can combine them, but you don't have to. And it's actually pretty clear that most people don't. And I don't think the future of the metaverse is that they're always going to come together, which is sort of a matrix idea. Because that's why so many companies are doing all of the AR, augmented thing where you can still see through if you wear the glasses. Because it's clear that having that kind of 360 immersion in a virtual world can be super cool, but probably not all day long, at least for most folks.

Liam: Out of curiosity, what do you think the implications would be of widely adopted augmented reality in the actual world?

Tom: It's so hard to say because so often with these kinds of things, companies will come up with use scenarios and then what people actually do with it is so different. And if you look at the history of technology, which I'm very interested in, you see that. When the iPhone first came out, people thought you'd hold it up and talk on it and everyone was worried about brain cancer and people didn't really even think about apps or that it'd be connected to a watch or whatever. And so often uses are emergent from new technologies. And so there's a whole bunch of predictions out there, but if history is any guide, they're mostly going to be wrong. And the really cool stuff we're going to really want to sort of be watching to see what it is that folks do with these things. The big warning around all of this stuff is that you could have this stuff being largely developed by governments or nonprofit organizations, but that's not the world we live in. We live in a world where the Metaverse kinds of technologies are overwhelmingly being developed and implemented by for profit corporations. And so what is being talked about in terms of what is going to be used for is very much driven by a certain kind of commodity product mentality of those companies. Which is probably just scratching the surface of what could actually happen. And so right now that kind of prediction stuff is very much being driven by marketing and it's very much being driven by for profit corporations that probably aren't going there in all kinds of directions of cool stuff that could be done with these technologies.

Liam: I think that many of the things that we're seeing predicted, there was a video circulating recently, at the time we're recording, of someone shopping for I think a bottle of wine in a store in, again, NVR. But I think that many of the things that people are thinking of in terms of the notion of having property, the notion of buying things, the notion of creating things have already played out in Second Life in a certain way.

So I want to talk about a concept that you established in your book, Coming of Age in Second Life called creationist capitalism. Because I think this idea that the world that we're talking about is actually a space in which you can do things and in which you can create things although it is a creation itself is really interesting and something that should be talked about as we revisit the idea of existing in this space.

Tom: Yeah. So a couple great points you mentioned. One is that one really negative effect of the corporate hype around the Metaverse, but around this stuff more generally is a lack of attention to history, which is very common in that hype. And it's amazing, Second Life is almost 15 years old now, and it's amazing how many people will be surprised or say, how can you still be doing stuff in Second Life, it's old.

And no one ever asked me that about Indonesia. No one ever says, why do you still go to Indonesia, why are you still interested in Indonesia, Indonesia's really old. You should only be studying new things. And that idea that we're only interested in what is new or big is definitely coming out of that pipe of the industry that can damage our research agendas in that way.

And this idea that people will often ask about, is this going to take over and have a billion users or should we just pack up and go home without any idea of a middle ground is also I think damaging. Because there's so many interesting things going on let's say with virtual worlds that have between a half million and five million active users. That's a lot of people. But part of the hype cycle is, if you're not going to hit a billion then I don't care.

And so I think thinking about looking at the whole range of things that people are doing online, not only the top two, is very, very important because often a lot of pioneering and interesting stuff is happening in smaller spaces that aren't getting noticed by the tech framing of these things.

And that idea of creationist capitalism is also really interesting and important because, especially right now, this moment that we're in around the Metaverse, not everything is new. A lot of what's going on is not new, but some of it is new. But it's really hard to tell right in the moment what is actually new and what's not, it's surprisingly difficult. That's always the case.

After five years, it's easy to look back and say, oh, this part of it was innovative and new and this part was not. But right when it's coming out, it's remarkably difficult sometimes to figure out what's new and what's not.

So the creationist capitalism thing is just thinking about, in the most basic sense of thinking about economics, going back to Marx or going back to basic economics, commodity production requires materials and labor, so if I'm going to build a house or a chair or a car or something, I need human labor to make that. And then there's the materials, I need cloth to build a shirt or a coat, I need metal and plastic to build a car, I need wood or whatever to build a chair. And the commodity models of economics are based around these factors of materials and labor and other things as well. But those are the big things, time and other things show up as well. But materials and labor are the big stuff.

And with creationist capitalism, what I was trying to think about is that with online commodity production, you really lose in many ways that material side of it. And so creativity itself becomes a new kind of labor in a virtual world, whether that's Fortnite or Decentraland, you get cool gear in Fortnite or you build something in Minecraft or you build a chair in Second Life. To make a thousand copies of that chair or one copy of that chair is almost no difference, just a teeny amount of bandwidth and server space. But you don't need a thousand times the materials like you do if you're making a thousand chairs.

So creationist capitalism is a way of thinking about what happens to capitalism when that materiality shifts. There's still the materiality of the computer and the keyboard, but there's not the materiality of what's needed to actually make the commodity in the same way.

And so we are moving into a world where, there's still going to be physical objects sold, lots of them, but there's a lot of stuff nowadays being sold that is virtual. And the NFT, the non fungible token thing, is part of that. Part of what an NFT is doing is actually trying to break this model of creationist capitalism. It's worth more because of scarcity, there's only a few of them.

And for 15 years, in Second Life you can do that. So if you make an object, a chair in Second Life, you can have it be free to copy or you can say this is unique, it can't be copied further. And you are basically turning it into an NFT then. And that interrupts that scarcity model where the same cost to make a hundred or to make one. So NFTs are basically trying to recreate the scarcity of physical objects where you need more wood or more metal to increase the value. It's that same idea.

So yeah, I mean, there's more to creationist capitalism than that obviously. But to me, one interesting piece of it is this issue of digital objects for which the materiality cost of their production is zero or close to zero compared to the physical objects.

Liam: I'm curious because it strikes me, and I think this comes through in Coming of Age in Second Life as well, that this mode of material-less creation or creation that is not as intensive on materials has huge implications for your experience of the virtual world, but also can reflect back into your experience of the actual world. Specifically in how you design your own embodiment and environment in a virtual world. So I'm curious about your thoughts on that. And also from a philosophical perspective, if the manufacturing of scarcity has an impact on that and what that impact is?

Tom: Yeah, I mean, that's a deep question, so I don't really have a complete answer for that. But it is true that because of the lack of scarcity in that sense, often people in a virtual world, their homes are palaces or they're really big, or they can have 10 cars, they can have a virtual Ferrari. And there has been interesting thinking about how is it that you can have a shift in social class in that sense.

But then also the other side of that, once again, I'm not the first person to say this kind of thing, is could this then, if it's not done right, lead to a world where rich people have a big house and a yacht in the physical world and less rich people have a pod or a small studio apartment and they have a yacht and a mansion online. And is that a way to shut them up because they don't get to have equality in the physical world.

So you can imagine this as being a way to exacerbate or increase class inequality. Or not. It's not really inherent in the technology, as with so many of these things it's what we do with it. And so it is interesting how we think about scarcity and abundance, and the way in which NFTs are trying to reintroduce scarcity into a virtual environment that, historically, one of the selling points is you don't need it. You don't need to have scarcity. But because our economic models are predicated on scarcity, then how are things going to get expensive if everyone can have it, right? And one point of view would be, who cares? Let's let everyone have stuff. Another can be, if I'm thinking in that capitalist model, or I need to make money, and the only way I can think about that is through scarcity, then I have to try and artificially create scarcity in a virtual space, because that's the only way I can think about money making.

So it's a really interesting question, once again, about how our economic models are intersecting with these new technologies, especially, once again, given a context where it's not, when you think about VR or virtual worlds, these metaverse spaces, it's not like you have five big corporations going up against like five nonprofits, a nonprofit consortia all doing it and seeing what happens. It's all corporate, and so we really have to push back and be creative to think about these other kinds of things, because the nonprofit space online, the kind of Wikipedia, Internet Archive, other kinds of things that are out there, nonprofit stuff, it's out there, absolutely. But it is very much overwhelmed in the public discourse by the corporate stuff. It is much, much bigger.

Sometimes, when people say, "Oh, the technology causes X, or the technology is doing X," we need to step back and say, "The technology when viewed through this capitalist model does X, but we can think otherwise. That's not the only way this technology could be used." And that's going to be a real challenge moving forward, unless there's some big movement to sort of think of these things more on the line of utilities, where we really want to support non-corporate models for them.

Liam: In a previous episode of the show, I talked to Kerry Murphy, who runs a studio called The Fabricant, and The Fabricant produces virtual couture, so fashion that only exists in virtual space, and you can apply it either to a photo of yourself or to an avatar. In Kerry's case, he had a photorealistic avatar created, and in the episode, we talked about how he tried out programming this avatar to do certain dance moves or wear clothes that he would never wear.

So I'm really interested in this idea that I think you also get into in the book about how this mode of creation in virtual space allows you to embody yourself in ways that are perhaps wildly divergent from the embodiment that you have in the actual world, and what that means to people and the implications that it has when you can kind of design yourself?

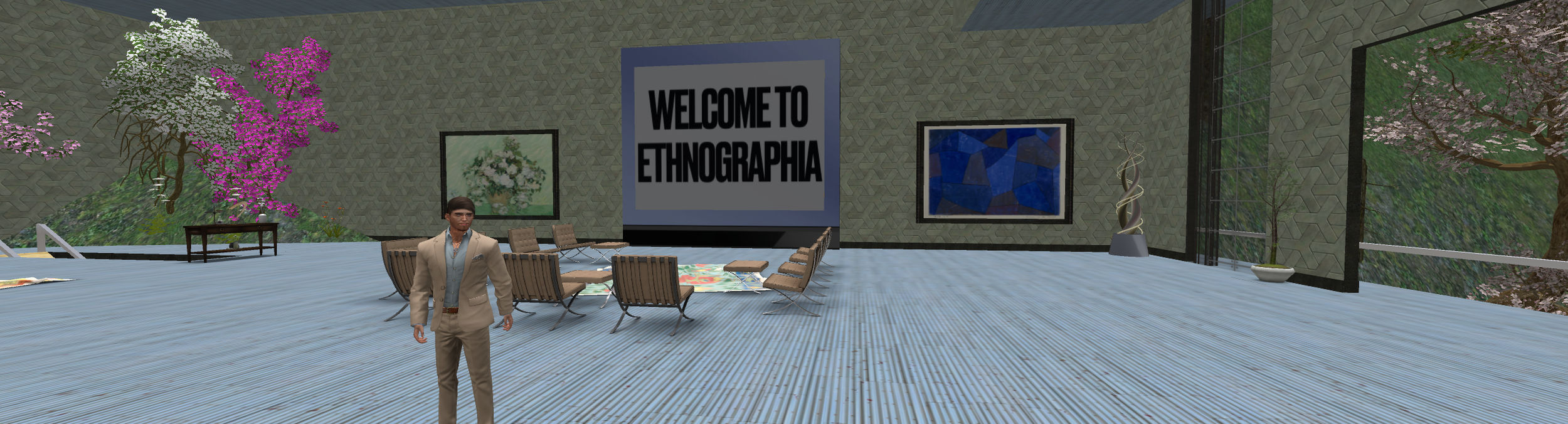

Tom’s Ethnographia in Second Life

Tom: Yeah, no, it's a super interesting question, and it's something that is really affected by the particular kind of virtual world in question. So some virtual worlds, and a lot of the biggest virtuals out there are designed as games, right, like World of Warcraft or Fortnite or something like that, and often, in those virtual worlds, there are fairly strict limits placed on your avatar embodiment. If you are in a Star Trek virtual world, you can't be a hobbit and you can't be Darth Vader because it's supposed to be Star Trek, not Star Wars, right? And so there are limits, and often in those spaces, avatar customization is often more about clothing or weapons, gear, stuff like that.

And then there are virtual worlds that allow you to look almost any way that you want, and so in a virtual world like Second Life, you can be photorealistic. You can also be a refrigerator or an animal or a ball of light or a different gender or between genders or a dragon. So some of them are very open ended and some of them aren't, so that has an effect. And another thing that has an effect is whether you're allowed to have one avatar or more than one avatar. So in Second Life, you have one avatar, but you can have as many free Second Life accounts as you want. It's just like getting Gmail accounts or something like that.

And so most people in Second Life have multiple avatars, and they'll call them alts, and sometimes a common thing that will happen is someone might have an alt that is closer to their physical world embodiment, and then another one that's more different for sort of fantasy purposes or for fun, they want to be another gender, that kind of thing. So if you only get one versus if you can have multiple, that's also going to change what people do with them.

And so you see all kinds of amazing creativity around that kind of embodiment, whether that be people who think they might be trans trying to be the other gender, and maybe that helping them understand themselves. There are support groups that happen for that kind of thing. People who identify with animals and love animals being animals, people who want to be younger or older than their physical world embodiment. I've worked with people in Second Life who are in their eighties, and they sometimes embody as a avatar who's 20 years old. In several cases, I've talked to people about that, where they say, "I'm not trying to hide who I am, but I don't want people to know that about me at first," because they love going to a dance or going to a club and having people talk to them and dance with them and whatever, and then if they ask, "Oh, who are you? How old are you?" they'll say, "I'm 82."

But they'll say, "In my physical world, that same person just would walk past me on the street and not even talk to me or look at me. But if they meet me and they talk to me, this 20-year-old body is actually, in some ways, it's who I am. I used to be this old, and I think this is some way the authentic me." And people just, I had one person say, "It's like you take a zipper and pulled me out, and that's who I am. And I love it, because I'm not immediately dismissed for being 80 years old. People get to know me, and then I tell them." And so there's also that interesting kind of thing that can happen socially, where people can be so quick to judge people based on their race, based on their gender, based on disability, based on age, and to not be immediately judged on that, people... One person in Second Life once told me, and this is in my book, where in Second Life, you get to know people from the inside out, instead of the outside in.

So that kind of thing is really wonderful. And then in some virtual worlds, yes, you can not only have clothing, but you can make and sell clothing, and in many virtual worlds, that can be a real source of income. And one thing that's from, it's not in my Second Life book, in some of my more recent writings on disability, one person I worked with was a fashion designer in the physical world who had to stop because of a disability, because of Parkinson's disease, and sort of just stumbled into Second Life just to check it out, and realized that she could actually do fashion in Second Life. So this is another example where we can't often predict what the use will be.

And she started making money in Second Life, some pretty good money in Second Life, and is now a very well-known fashion designer. But for her, it was also this huge emotional thing of being able to reconnect to a career that she thought she would have to get rid of forever because she could no longer hold a needle or do that kind of stuff, and she was able to bring back a creative side of her life that really meant a lot to her. And on top of that, one thing she really found interesting, having been a professional fashion designer, is that in Second Life, gravity works differently. Avatar bodies work differently, fabric drapes differently, and that was a cool challenge, and is a cool challenge for her. And I know people who are architects who had to quit their jobs, and love building homes in Second Life as well.

But yeah, so the avatar embodiment kind of thing is really interesting. And unfortunately, we still see racism and sexism and ageism happen in these spaces based on avatar looks, but it doesn't have to be that way, and there's also a lot of people pushing back against that and trying to think about new kinds of inclusive communities that we can build through avatar embodiments in these spaces. And so it's going to be a really interesting area moving forward, because in theory, you could have a virtual world that didn't have avatars, that people just sort of looked around and were ghosts, but it basically never happens. And so it is a really interesting area to watch as we move forward, and once again, how do people do different stuff with them based on the degree to which there's flexibility or multiplicity?

Liam: Right. And I think that that whole discussion highlights another point from your book that I thought was so important, which is that when we think about corporations coming into a space like Second Life and their motivations. What they would actually find out is that this mode of creation is the consumption that people are interested in, that creation is the mode of existence in that space, right?

Tom: Yeah. Well, and that idea of user generated content has become huge because YouTube doesn't make the videos, Facebook doesn't make the posts, Twitter doesn't make the tweets, and so a lot of these companies are based on a user generated content model. And in virtual worlds, open ended ones like Minecraft or Decentral and Second Life, that kind of thing are doing that. Ones like Fortnite or World of Warcraft that are more game oriented have less of that. The company is doing more of the content in the game oriented ones, but the more open ended ones actually share a lot with things like Facebook or Instagram or Twitter in that it's based on a user generated model where the company isn't creating most of the content.

The interesting distinction with something like Second Life, and this shows up with the game worlds as well is the current corporate model around the metaverse, the sort of two big paths, the two main ways that they make money is either advertising or subscription based, and a lot of games are more subscription or purchase based. So you buy Zelda: Breath of the Wild for $59 or you buy League of Legends or you buy Red Dead Redemption or whatever. You purchase the game or you pay $10 a month for it or whatever, and Second Life is free but to own land, you pay a monthly fee, so it's also subscription based, and that's one model. And then the other model is the advertising based of the free things like Facebook or Instagram. And what's interesting is that with the subscription model, and they both have whatever, pluses and minuses, but with the subscription model, you don't get the surveillance capitalism kind of thing.

Second Life doesn't care if your identity is different and they aren't tracking everything you do and spend, and the online games aren't doing that in the same way as well. Animal Crossing isn't doing that in the same way because you pay 50 bucks to have Animal Crossing. That's how they make their money. And so those are the two main forms that it is taking and both of those can use the user generated content model. So Facebook does it or Twitter does it and their advertising based, where something like second life does it but they're more subscription based. Online games are more subscription based. It's more of a Netflix model in that sense. And so it's going to be something very interesting and important to watch moving forward is what are the effects of those different commodity models? One subscription, one advertising. And then we can sort of make a grid, how does that then interact with the degree to which a virtual space is using a user generated content model or a company made model?

And there's an in between model that even Second Life uses a lot that a lot of these places use, and this shows up even with things like YouTube nowadays where between the company and the average user is the content creator or the influencer. So you have the idea that because like in Second Life, I mentioned that person who creates clothes and sells them or whatever, we're talking one or 2% of people in Second Life who are doing that kind of thing, and then there's a bunch of people who just hang out and buy the clothes. Think about YouTube. You have people who make a lot of money doing YouTube videos and they aren't employees at the company, but they are paid actually, some of them a lot and then you had the average person who watches it.

So you have a kind of hybrid third model that is showing up in a lot of these spaces where it's not the company making it the stop, like Nintendo for Animal Crossing, you get the rollout of the new content they're making, or the user, the average person making everything like tweets or Facebook posts, where you have this in between kind of semi-professional position of the content creator or influencer who's not an employee of the company, but in many cases, is paid by the company or by the users and often ends up creating most of the core content so the company doesn't have to and the average user doesn't either, and it's the average user that levels up. Maybe they get into it and they become content creators. So it's interesting how that model has also emerged as a third model, and how will these different models shape what happens socially is a really interesting area to be looking out for as we're watching what happens with these things moving forward.

Liam: For sure. Is that one of the things that we can expect in your work on the metaverse?

Tom at his desk in Second Life

Tom: Probably. I'm still figuring out where I will go with that, but all these things I'm mentioning are things that I probably will be looking into. What are the different models out there? What are some unexpected models that are out there? What are some possibilities that we can look at with these things? Because Jaron Lanier, who's very well known sort of coined the term virtual reality, and one of his books talks about the idea of lock in, that we still type HTTP for a website or we still talk about a desktop with folders and that kind of thing, and that once a format gets locked in, it can be influential for years and decades. And so it can be really important to be asking these kinds of questions and doing this kind of research now while the stuff is a little more unstable and emerging, and we can try to steer it and think about how can we do it better, rather than wait until things get locked in and one format or one company wins out.

And then we see now with things like Facebook where it's way more difficult to change it once it is so dominant and locked in, that it's hard to imagine an alternative and it's hard to imagine how it would be implemented, even if we imagine it once something has become so dominant. And so I think it's really important to be having these conversations and thinking about these possibilities while things are still a bit more emerging and unstable and there's the potential to steer the conversations in ways before that lock in happens.

Liam: All right. Well thank you again, Tom, for joining me.

Tom: You're most welcome. This has been a lot of fun. Thanks so much.

BJ Best, Poet, ArtyBots

Poet BJ Best on teaching computers to do what humans can’t in the name of art.

Poet BJ Best on teaching computers to do what humans can’t.

In this episode, Liam speaks with BJ Best, a poet who teaches computers to do what humans can’t in the name of art. His network of ArtyBots is part of a vibrant scene of robots creating, sharing, and collaborating with one another on virtual art. In the interview, Best describes the reflective opportunities and editorial impact created by a bot-created body of work numbering in the tens of thousands.

Liam Spradlin: BJ, welcome to Design Notes.

BJ Best: Thank you very much.

Liam: So to start out with, tell me a little bit about your current work and the journey that led you there.

BJ: Yeah, certainly. My home discipline as I like to call it is poetry specifically, but recently I've been very interested in how computers can media art in a variety of contexts. Growing up, I was always interested in computers and am kind of a self taught programmer. I learned how to program using basic. And I was always interested in the way computers think and of course that's kind of a misnomer, computers themselves don't think, but they can do surprising things that, um, otherwise, humans can't. BJ: And so I always enjoyed dabbling, but it feels like only recently computers have become both accessible enough and also powerful enough where people like me, who don't quite know how to program entirely, are able to use them, um, in a variety of contexts in order to generate content. And so in the past couple years, I've used computers to generate art in a variety of ways. Um, procedurally generated music, I've created procedurally generated video game, I've worked with poetry and artificial intelligence and then, uh, the arty bots project to make computer generated art.

Liam: So, tell me a little bit about arty bots. What is that and how did you get started on that specific project?

BJ: Yeah, so arty bots is a Twitter account itself, but it's also the kind of umbrella term for a family of Twitter bots, all of which create visual art in a variety of ways. They're mostly abstract bots 'cause it's difficult to create representational art through mathematical equations.

Again, I was interested in the idea of how computers can do something that humans can't, and specifically when I talk about humans, I'm mentioning myself (laughs) uh, because I have very little artistic ability in any sort of traditional state. I cannot draw, I cannot paint, I've attempted these things and the results are fairly comical (laughs) as a result. But I love art and I love the possibilities of creating art and specifically I love modern, post-modern art, particularly bright colors abstract art, and that seemed to me like the sort of thing that a computer could do fairly well.

And so I got this idea in my head maybe I want to use a computer to make art. And so after a lot of searching around on the internet, I was able to find people who had ideas about how to do this and I was able to find some sample code as well, which helped make this to be a reality. After that I had to learn, uh, these bots are written in Python, I had to learn Python. I'd never done anything in Python before, and I wound up stealing codes from other people both to start making the art and then the second part, which is to create the image, but then also post it on Twitter in order to make it a complete bot.

And then once I had bots that were posting images, I figured it made sense to have them reply to each other as well with the various algorithms that were programmed within each individual bot. Liam: So you created these bots that are now creating visual art and I think there's an interesting question here, which is are the bots artists? Are you an artist? Is it both? Is it neither?

(laughs) I, I think it's both, although I would prefer to credit the bots maybe more than myself and I think the cool thing about the bots and the thing that might make them artists is that they can do things humans simply can't. The bots treat an image pixel by pixel as something and so most of 'em are 500 by 500 and so you can do the math and it would be very difficult for a human to concentrate on that number of individual squares and have each one be meaningful in some ways. A computer, of course, can run through a grid like that very, very quickly.

So example, for one bot, it's called Arty Abstract and it's one of my favorites and it paints very abstract pictures based on mathematical equations. Um, it uses things like sines a lot and cosines and other limits and logs and all sorts of interesting things to create an equation and for every color on the canvas and in computers, colors are usually defined by three different variables, I always use RGB, red, blue and green. Each one of those has a complicated mathematical equation and so each red value, green value and blue value are calculated by these equations and then each single picture is plotted. To ask a person to do that seems like that'd be remarkably difficult thing.

And so I think they are artists in the sense that they can do something that humans can't and ultimately they're the ones that are creating the pictures. Obviously I... there's a human behind it choosing the code, choosing the equations, but like I said, without the computer, I would be unable to present any sort of image like this and I feel they kind of have a life on their own in terms of the things they're able to create that someone through traditional techniques would not be able to.

Liam: I'm very interested in the definition of a concept like art and the definition of a perhaps more specialized kind of art called design. And so I think it's something that everyone has a different answer for but I want to know, like, does this method of creation or the creators themselves, do these things inform or change your conceptualization or the broader conceptualization of what art is?

BJ: I think it has to in some ways because up until this point in history, with some exceptions, the idea that there could be something that could do calculations and that could present something that looks like art were limited in a variety of ways. And especially as we approach things like artificial intelligence, my thoughts are pretty simple compared to artificial intelligence. It's surprising what AI can create that looks in some ways to either realistic things or perhaps more artistic than just pretty colors in terms of pixels on a screen.

That being said, it does really challenge the idea that is it possible that only humans can make art and what forms of art are acceptable? I know the challenge of claiming an art is created by a Twitter bot is that tweets kind of by their nature are very ephemeral. You see it for a moment, you either like it or you just scroll right by it and then for all intents and purposes it's gone.

Most of these bots, I was doing some brief research, most of these bots have tweeted around 60,000 times, more or less. Uh, the arty bo- arty bots bot itself is, is over 100,000. And each one of those is a picture. And so the question because, well, what do you do with so much art? (laughs) As opposed to should you go into a museum and a museum might have a lot of pieces, for example, but it's no where on the order of 60,000 different things you could conceivably look at.

For me, personally, there is this interesting idea too, that you can take any image created by one of these bots and present it on a wall, on a canvas, and I've done that. Recently I had a show about computer mediated art with a colleague of mine, Joel Matias who's a musician and we both created computer mediated art and one of the things on the walls of the gallery that we created was a conversation of arty bots and so I took 15 canvases created by arty bots and hung them on a wall in a very traditional setting.

And so that kind of further confuses the idea of something that otherwise is ephemeral and to give it to sanction of printing it out, putting it on canvas and hanging it on a wall.

Liam: You made a point about the fact that each of these bots has tweeted out thousands of times and created thousands and thousands of works each and I'm interested besides sampling one conversation, if this huge output somehow forms a larger collection are a cohesive body of work overtime? Are there through lines in these works or do they tell some kind of story or is there an additional meaning that's created through this constant additive process?

BJ: The analogy I think that makes the most sense to me is the idea of a museum or a collection that someone might have and that this is just a very, very, very large (laughs) collection of a variety of pieces and yet they're all done by the same artist, so to speak, and they're done by people in conversation.

Now, honestly that's a great question because I still don't know what to do with the idea of what would you do with 65,000 pieces of art? And that's just one bot and the number of bots is in the teens now and so again, the math quickly multiplies.

I'm not sure because it's challenging to say that the bots have grown or developed because the algorithms that I've devised haven't really changed. Once I think something works, I just let it go and, um, the oldest of these bots is now older than four years old which is actually comparatively ancient in terms of Twitter times and Twitter bot times. And so in some ways I like to think of it as the bots are continuing to do themes and variations of what they've done all along. But I do think it's important to think about, that these bots have had a long lifespan and enough interaction with each other and with other visitors that like to come and see them that there is something more cohesive and more important, that the sum is greater than its parts rather than just one pretty image that one tweeted out once upon a time.

Liam: Talking about this indirect or procedural process of art creation, I'm reminded of something maybe mechanically simpler, but no less sophisticated which is some of Sol LeWitt's work, which the work that a visitor or a gallery goer might see is actually the result of the gallery following instructions for how to paint the gallery walls and I wonder if you also consider the code or the procedure behind these works to be a type of art itself.

BJ: Yes, uh, I was thinking about that as well and I agree with you 'cause I think the similarities are very strong. The code is simply a set of instructions and then I'm asking the computer to carry them out in, again, complex ways or going pixel by pixel down the screen. I do think code can be art. I'm a little hesitant (laughs) to call my own code art though, and it's often because I feel like I'm mucking around and trying to create something almost sometimes to the point where I don't quite understand how it works. And again, as I mentioned, I often steal code that I find online because I don't quite know how to make something work and I'm very grateful to people who post examples online that I think I can take work and tweak and figure it out.

So personally I find my code to be, you know, they call it spaghetti code and I do (laughs) not follow best practices in a lot of ways which I'm sure will haunt me at some point. That being said, I do think there's an art to good coding and I think the people who can do it well, it is an art form because it's, it's working in concert with the machine to make the machine do something, um, incredible and very well. But it is a collaboration. Um, and the most basic example would be a random number generator. Any time you ask a computer to roll a die, you never know what number it's gonna come up with, and in theory you could do that yourself but the numbers a computer can generate are huge and it's so easy for it to do that you need that collaboration and you need the code to make that happen.

Liam: I also want to talk a little bit more about how the bots interact with one another because they are kind of replying to each other and passing these pieces back and forth and doing different things to them, but they also talk to each other as well and seem to have their own little personalities and I'm really interested in what that adds to the whole space.